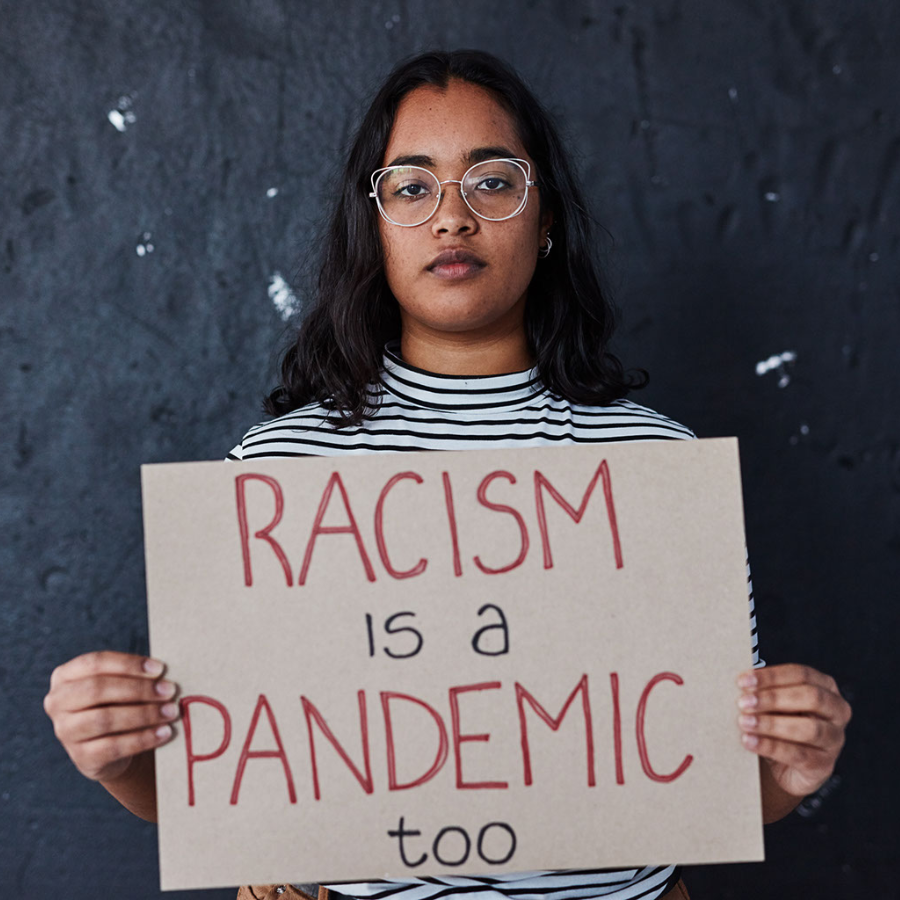

The COVID-19 pandemic is shining a spotlight on the current and historical racial disproportionality of health outcomes in the U.S. The unequal impact of the novel coronavirus on Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) reminds us of the need for robust public health responses and infrastructure to address our most pressing public health crises.

A public health crisis is something that impedes individuals and communities from being healthy. Historically, opioids, chronic disease, and gun violence have been named as public health crises because each of these hurt and/or kill people and limits their ability to live well and thrive. Behind many of these crises are systems and system-driven conditions such as poverty, inequitable access to housing, underemployment/unemployment, and more.

The devastating impact of the pandemic on communities of color has prompted a new examination of public health crises leading to over 90 cities publicly declaring racism a public health crisis in 2020. As part of a discussion on this effort by cities, towns and villages, the National League of Cities convened a panel of experts during our 2020 City Summit conference to discuss “Racism as a Public Health Crisis” featuring Dr. April Joy Damian, Associate Director of the Weitzman Institute, Dr. Georges Benjamin, Executive Director of the American Public Health Association, and Mayor Lioneld Jordan of Fayetteville, AR.

Dr. Damian describes a crisis as “the turning point of a disease when an important change takes place, indicating either recovery or death. A crisis signals a critical inflection point that is a matter of life or death. It is abundantly clear in the U.S. that racism is lethal to Black Americans, to Indigenous people, Latinos/Hispanics and other people of color.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the underlying issue of racial health disparities due to environmental racism, food apartheid, and a lack of equitable healthcare and exposed racism as a public health crisis in its disproportionate impact on Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC).

“At the end of the day, [racism] impacts your health. Poor housing, lead exposure, injury, poor schools. We know that high school graduation is a determinant of health. We know that women who have a higher education – their children are much more likely to live beyond their first year of life. A range of things from the social determinants of health that make an enormous difference,” said Dr. Benjamin.

In June 2020, the Pew Charitable Trusts reported that: “Being [B]lack is bad for your health. And pervasive racism is the cause. That’s the conclusion of multiple public health studies over more than three decades.” They quoted Dr. Benjamin, who asserted that “We do know that health inequities at their very core are due to racism. There’s no doubt about that.”

The framing of racism as a “public health crisis” is a somewhat recent development for cities, towns, and villages, but it can create urgency around the fight to end racism across our local policies, practices, and procedures. To date, more than 90 cities, 65 counties, and five states have declared racism as a public health crisis and several more are mobilizing to make this public declaration.

To date, more than 90 cities, 65 counties, and five states have declared racism as a public health crisis and several more are mobilizing to make this public declaration.

Dr. Damian notes, “Positioning the long-standing issue of racism as a public health crisis is not just a matter of semantics. Framing it in this way compels organizations and government units to address this crisis in the broad, systemic ways that other threats to public health have been addressed over time, as we’re seeing with the current pandemic.”

Local leaders have the power to listen to their marginalized and oppressed communities, especially poor, BlPOC, LGBTQIA+, and disabled women and gender-non-conforming people, and center their lived experiences to address this crisis. Mayor Jordan said he did just this in Fayetteville.

“When I sat down with my African American Advisory Committee, we began to have conversations that might have been a little uncomfortable for me and for one another. But we’re getting to the truth and the facts. Why don’t African Americans have decent housing? Why don’t they have the same education as white Americans? Why are they making less in wages? We have to do something about that. We need to make sure everyone can clothe, feed, and educate their families.” Acknowledging racism as a public health crisis is a first step that can lay the groundwork for more intentional action and ultimately, policy change. These statements engage our local public health infrastructure in the fight to end racism. This designation can open new avenues to acknowledge racism as a life-and-death problem. Subsequently, a racial equity action plan that is developed with the inclusion of all stakeholders’ voices will lead to policy changes and targeted solutions that benefit all.