Our Stanford Legal Design Lab has spent the past several years working to develop new solutions to address the eviction crisis. We’ve been redesigning the documents that courts send out to tenants who are being sued for eviction. We’ve built new websites to help tenants know their rights and possible defenses to use in court. We’ve helped tenant advocacy groups create text message hotlines for people facing a housing crisis.

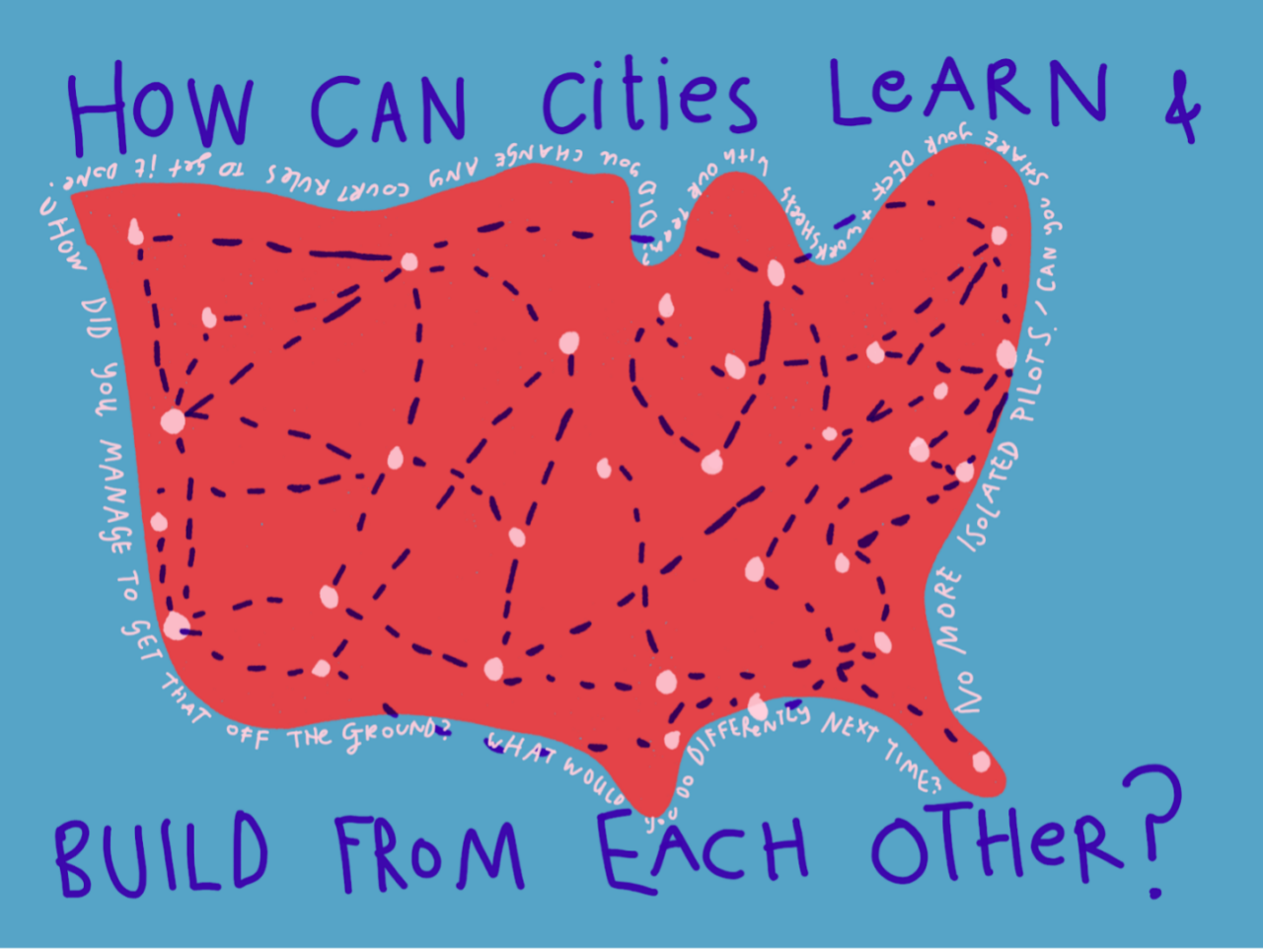

But in the middle of 2019, when we reflected on our work aiming to prevent evictions, we were struck by one major observation: Despite momentum by city leaders around the country to develop innovative solutions to the eviction crisis, most of this work was happening in city or regional bubbles. A county in Arizona, for example, may launch a new tenant help initiative, but leaders in Buffalo, Richmond, Minneapolis, or San Francisco wouldn’t know about it. Each city group had to figure out what the landscape of possible initiatives might be to respond to their local eviction crisis and then try to build, fund, and evaluate these initiatives, all on their own.

What if city leaders working on local eviction prevention were talking to each other? What if they could share their program designs, evaluation results, data strategies, funding plans, community outreach, and legislation drafting? What if initiatives piloted in one area could be replicated in others, saving resources, speeding up implementation, and achieving larger impact?

These were the driving ideas between our Lab’s initial discussions in 2019 with the National League of Cities. We had read about coordinated cohorts working on new policy initiatives like basic income programs. We thought that we might be able to build from this cohort model by working with a group like NLC that has a strong network of local leaders and aligned public interest priorities. We began to discuss how we might bring together a cohort of cities to work on eviction prevention in a coordinated way. Rather than focusing only on developing individual interventions in single locations, we wanted to see if we could drive a more scaled-up and strategic network of change-makers.

Now, at the conclusion of our first Eviction Prevention Cohort, we have seen the many policy, service, and technology innovations that have emerged in 2020. Many of these initiatives were spurred by the growing eviction crisis related to the COVID-19 emergency, but they also leveraged past years’ work by local task forces, government agencies, and civil society. (Read the full report about the cohort here.)

So, what have we learned about how evictions might be prevented? And what are the best practices to help tenants gain stable housing? In our discussions with local leaders, we’ve gleaned insights about effective eviction programs.

Our goal now is to amplify what we have learned to help cities and communities across the country improve programs that will help ensure stable housing for residents who are most at risk of eviction.

From Emergency Interventions to Permanent Programs

The pandemic catalyzed many emergency initiatives to address housing instability. Cities and communities stood up new rental assistance programs, passed temporary laws, implemented new policies, and built partnerships between providers both within and outside local governments. The emergency pushed action to address tenants’ needs so that many who otherwise would face eviction for unpaid rent were able to stay in their homes.

But how these programs will continue into 2021 is an open question. Cities and local governments do not typically have long-term resources or funding to continue offering robust rental assistance, mediation and diversion programs, or other emergency initiatives. How can communities fund and staff these and other new programs?

Securing sustainable funding is primary to ensuring that cities are able to maintain the innovative interventions of the pandemic era. Along with securing sustainable funding are many lessons from these new initiatives to better serve renters, landlords, and broader communities. The Stanford-NLC 2020 Cohort surfaced key metrics that cities should aim toward:

- Speed of Service: How quickly do renters receive responses after they apply for rental aid or eviction diversion programs? How quickly can a rental payment be calculated and then given to the person in need?

- Ease of Use: How easy is it for a tenant or landlord to find a service or program, or to learn about a law or policy? Are these laws, policies, and programs easy to comprehend? And once a tenant or landlord knows of them, how easy is it to apply, hear back, and follow through?

- Coordination of the Local Network: Do the community organizations, legal aid providers, government agencies, and courts have coordinated systems, at least from the point of view of the citizens? Are there warm and clear hand-offs between the different organizations? Are there streamlined programs with a single point of entry, or are programs dispersed, siloed, and disconnected from each other?

Ideally, 2021 will see both funding and improvements to the new range of eviction prevention programs serving communities nationwide.

The Eviction Diversion Model Ramps Up — and May Be Improved

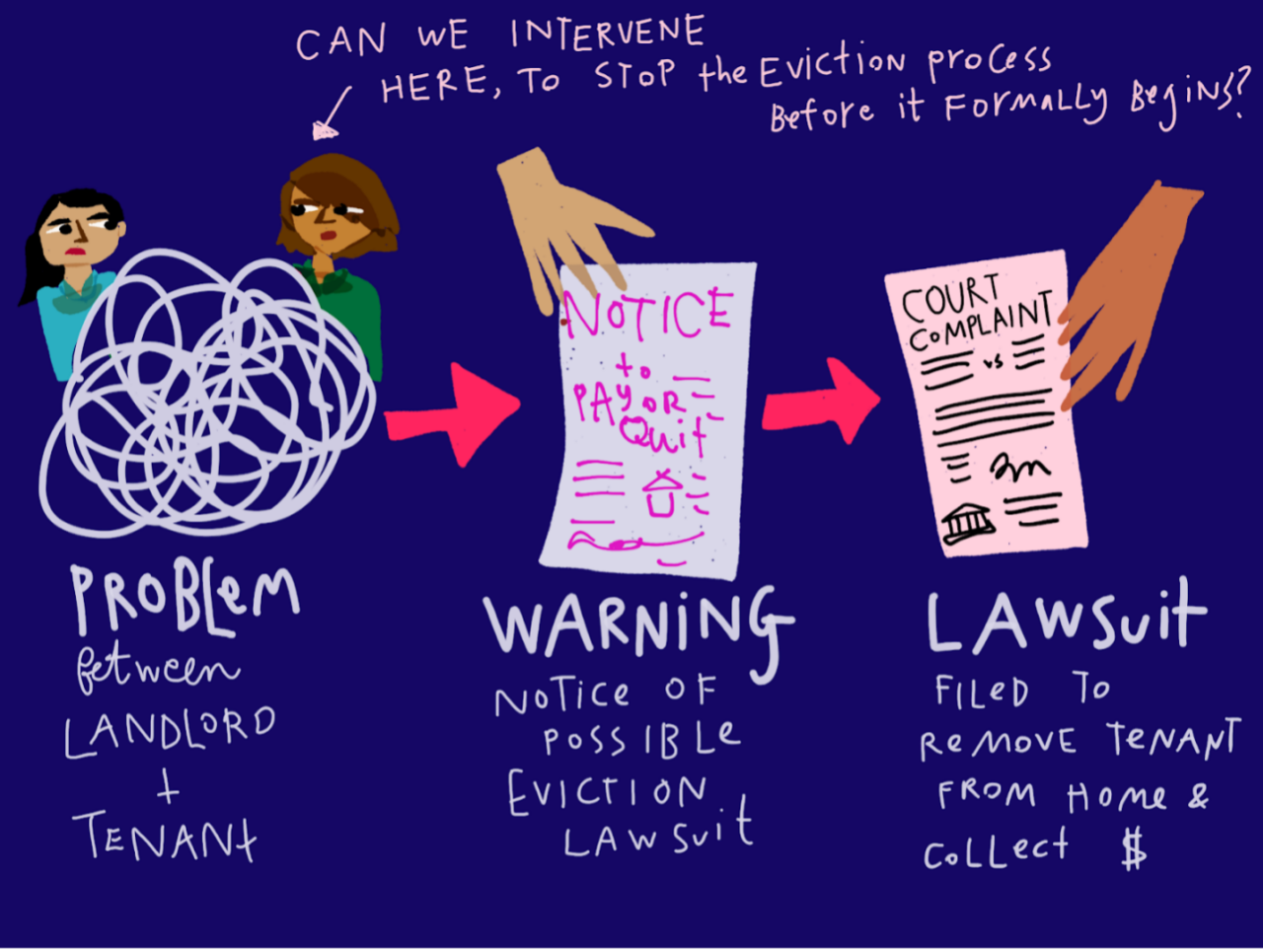

Eviction diversion or prevention pilot programs have become more common in the past several years. With the pandemic, many more regions launched eviction diversion programs of their own — and quickly. The eviction diversion model generally follows the following pathway:

- When a landlord files an eviction lawsuit against a tenant, either party can sign up to participate in an eviction diversion program (and the other must agree).

- The court or legal services agency hosts the program. Once the parties agree to participate, then they process their application to confirm they’re eligible.

- The diversion program staff helps the landlord and tenant through a mediation session to agree on a payment plan and possible other terms in a settlement agreement that will let the tenant stay in the home.

- The diversion program connects the tenant to other social services that might help them with their financial, employment, schooling, health, and housing situations.

- The landlord receives funds from the program to compensate for some or all of the unpaid rent.

- The court case is dropped, meaning that there is no official eviction judgment against the tenant in the court records. This prevention of a judgment may benefit the tenant down the road in credit reports, tenant screening, and other risk assessments.

- The tenant is allowed to stay in the home as long as the terms of the payment plan and agreement are met.

- Ideally, the tenant’s financial situation improves and they are able to continue living in the home, the landlord maintains the property, and the relationship follows the rules set out in the lease. Alternatively, the tenant is given more time to make plans to move to a new, more affordable home.

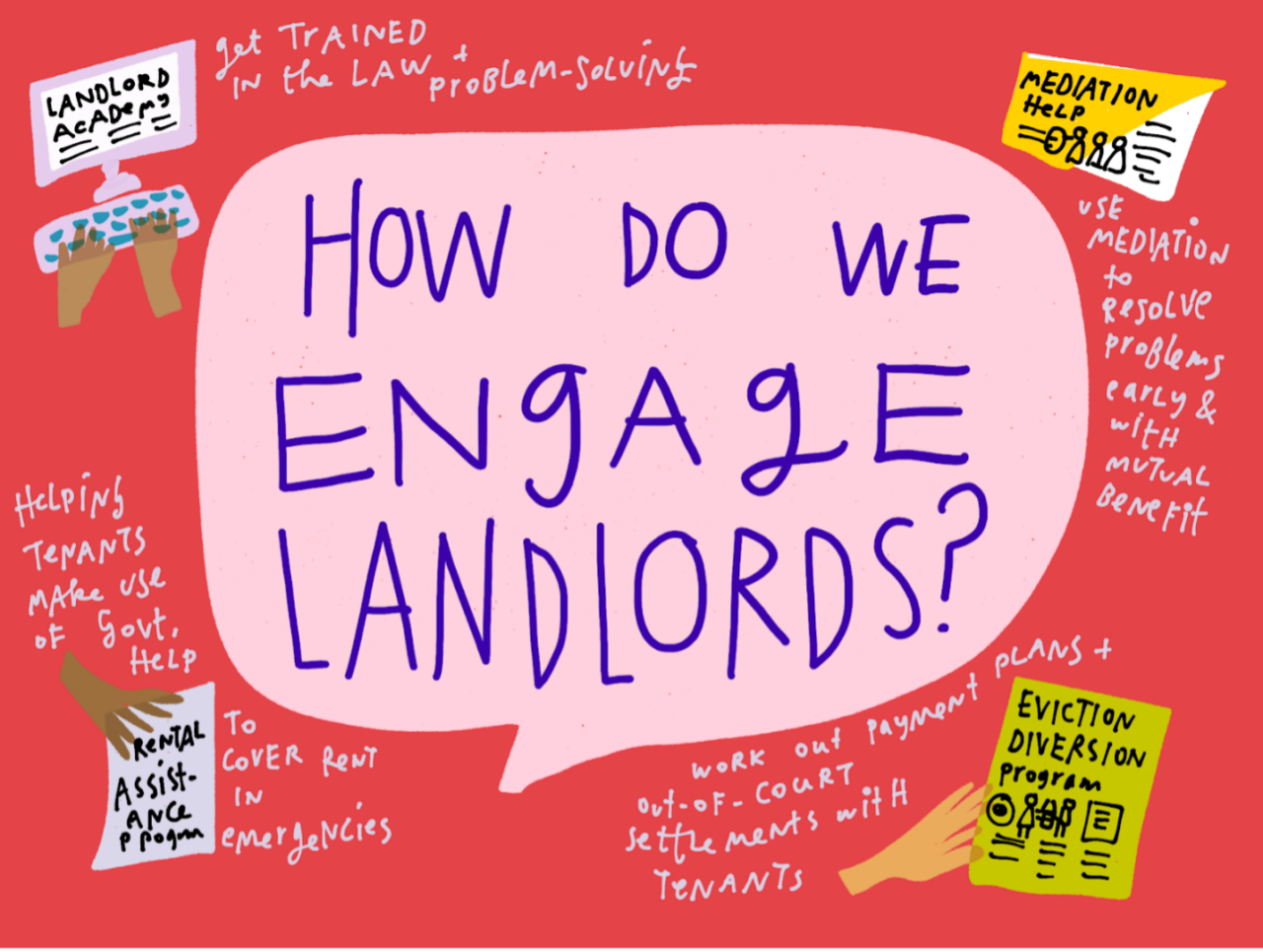

Cities across the country are beginning these programs in order to prevent eviction judgments, keep people in their homes, and repair tenant-landlord relationships. Some discussions from our cohort also point to ways that this basic model can be improved, made more effective, see greater participation, and achieve better outcomes, including:

- Earlier Intervention. Diversion programs may produce better outcomes if they are available before landlords file lawsuits in court. What if tenants and landlords were eligible for the mediation, rental assistance, and other services at the point when their problems begin to escalate? If the diversion program is available to them around the time of the ‘warning notice’ (sometimes called Notice to Pay or Quit), then they could receive services before a lawsuit is filed. This would save landlords the costs of filing and hiring a lawyer. It would free up court dockets. And it would protect tenants from having a court action against them that may impact their future housing opportunities.

- Navigators for the unrepresented parties. Even with a diversion program in place, tenants and landlords without lawyers may have trouble navigating the program, the court process, and the other available services. Having ‘legal navigators’ can help tenants and landlords stay on track during the process and give them a sense of control and empowerment so that they may take full advantage of the services offered.

- Court rule changes to accompany new services. States like Michigan not only implemented eviction diversion programs but also worked with courts to change the procedural rules to encourage more mediation between landlords and tenants. By requiring the parties to explore possible settlements before going to an eviction trial, the court can encourage and oversee more mutually beneficial, out-of-court settlements that can prevent eviction judgments against tenants and help landlords receive compensation.

- Community outreach — especially to landlords. How can we make more tenants and landlords aware of eviction diversion programs? Ideally, people would be aware of the program before their lawsuit, or early in the process. They’d know how it works, whether they’re eligible for it, and how it might benefit them. Right now, many programs use fliers to advertise. How can communities enhance their outreach efforts through online sources, in community hubs, and through trusted networks?

Outreach to landlords and property managers is particularly important. This is the case for eviction diversion programs, as well as for other initiatives such as landlord academies (like Rent Ready Norfolk) and rental assistance programs. These programs rely on landlord participation and agreement. If there is not effective outreach to explain existing supports and the importance of preventing evictions, programs may underperform because landlords — like tenants — are not fully informed and do not buy-in.

Conclusion

Cities and public interest organizations may deploy a wide range of initiatives to help prevent evictions. We are cataloguing profiles of such initiatives on the Eviction Innovations site. We have also documented many details in a recent paper, Approaches to Eviction Prevention (July 2020), which describes new policies, technologies, and services that might improve outcomes.

Now there is a need for ongoing implementation and evaluation of these new initiatives. The emergency period drove many new policy and service innovations. It also meant that resources were diverted away from larger movements toward Right to Counsel or systemic reform of the eviction system. In 2021, even as some of the eviction protections expire, there is increasing awareness of the importance of housing stability — and how interlinked it is with public health and children’s’ ability to thrive.

2021 should be a year of maintaining momentum in programs that reduce the number of people facing eviction lawsuits; it should be a year of increasing the financial and legal assistance available to resolve landlord-tenant problems; and it should be a year to identify systemic reforms to keep people in affordable, stable housing. The emergency of 2020 has shown how quickly new protections and services can be stood up. Now we need to do more research to refine and improve approaches to building more meaningful and long-term solutions to America’s housing crisis.

Read the Eviction Prevention Cohort Report

Learn more about the 2020 Eviction Prevention Cohort and explore key findings from the report, The Eviction Prevention Cohort: Highlights from the Five-City Pilot.

Apply to the Eviction Prevention Learning Lab

Gain exposure to best practices, policies, and tools to prevent evictions by applying to join the Eviction Prevention Learning Lab! Applications are due February 26, 2021.