Cities, towns and villages have a responsibility to ensure their public spaces feel safe, welcoming and accessible. The COVID-19 pandemic and 2020 racial unrest reinforced a crucial need for local leaders to apply an equity lens in making local decisions about structural systems and the built environment. Lacking resident engagement and empowerment in the neighborhood and public space development has led to gentrified areas and consequences for existing residents. These consequential trends are especially evident in development in neighborhoods where the majority of residents are of low-income status or Black, Indigenous or other People of Color (BIPOC). Reimagining public spaces can influence the health, economic conditions, transportation, housing and social outcomes of an area and its residents. Because public spaces can have such a profound impact on the surrounding areas, the process of reimagining them must integrate community engagement and resident perspectives.

Why Include Residents?

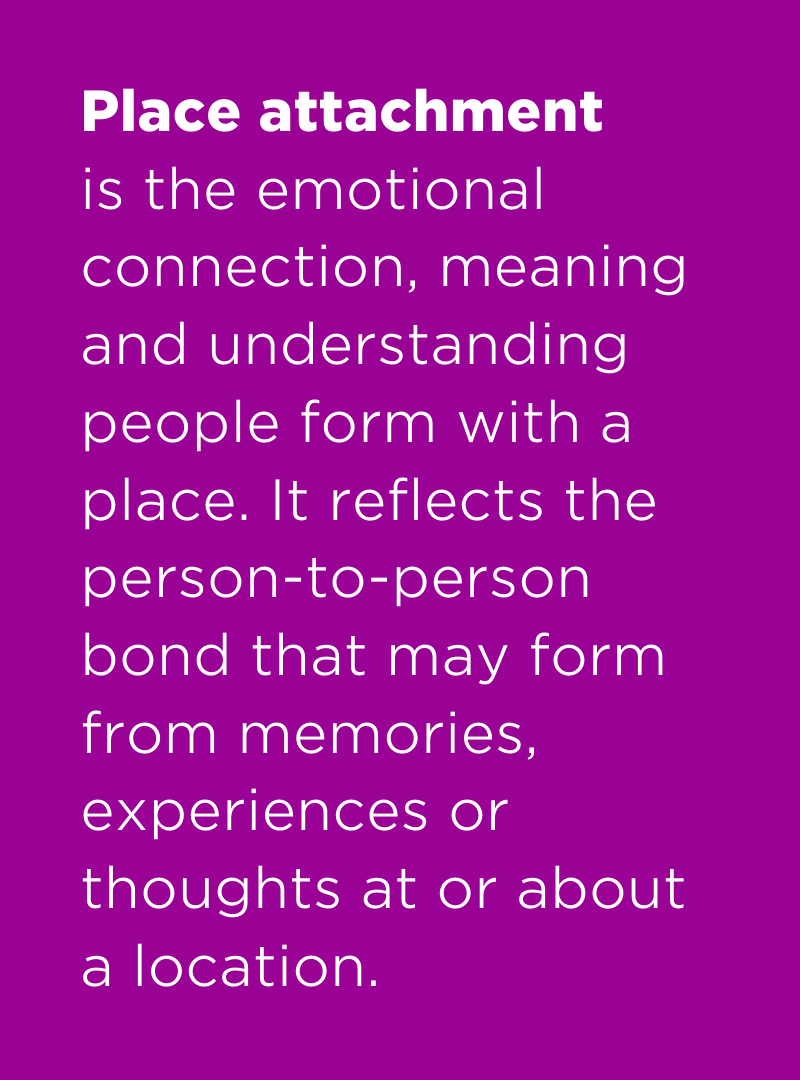

Including residents in the process of reimagining public space is critical to ensure places thrive. Empowering residents in the process and learning their desires increases the likelihood that a place is representative of community needs. A study of post-pandemic adaptive spaces found that places designed with residents’ interests, history and the arts received more regular visitors to the space. A place built with residents in mind can nurture their place attachment, increasing residents’ desire to visit a place, bring others to the place and support the place’s businesses. Building a trusting relationship between residents and local leaders not only benefits a specific project; it can foster civic engagement and better outcomes for future city endeavors.

Pandemic Lessons: Reevaluating After Quick Changes

The first year of the pandemic showcased local leaders responding quickly to support small businesses when operations could not continue indoors. Creative street and parking alterations enabled pop-up plazas, outdoor dining, curbside pick-up and more. These reimagined spaces, and the access to the outside world that they provided, acted as one of the few bright lights during the early phases of the pandemic. Local leaders now have a responsibility to review their street alterations to ensure they benefit residents of all incomes, abilities and relevant needs.

Ensuring Disability Access in Little Italy, New York

New York City launched its Open Restaurant program in June 2020, allowing restaurants to operate their services on sidewalks, parking areas and adjacent outdoor spaces. The initiative set a trend that spread across the country for reimagining public spaces to support small businesses, however possible, when indoor operations shut down. Local leaders were largely lauded for finding innovative ways to ensure businesses survive, and many residents notably wanted the changes to remain in a post-pandemic world. However, not all groups wanted these changes to be permanent. People with disabilities and advocates for people with disabilities spoke up about public space changes lacking accountability for alignment with the American Disability Act (ADA) guidelines. Several videos went viral, showcasing people with visual and mobility impairments experiencing challenges, such as a guide dog struggling to navigate through waiters and plantings on the sidewalk, a person in a wheelchair passing through narrow spaces between tables and a person with amputated legs needing to move into the street (while cars honked at her) because of crowded sidewalks.

Although Open Restaurants required businesses to meet ADA requirements, not all restaurants were complying. The Regional Plan Association, Tri-State Transportation Campaign and Design Trust for Public Space partnered to form an initiative called Alfresco NYC to ensure public space accessibility. They launched roundtable conversations with restaurant owners, residents, designers and other stakeholders to discuss design challenges and opportunities to improve accessibility. This collective facilitated the launch of an annual awards program to recognize exceptional outdoor dining and closed streets. Winners would receive a $500 prize to showcase innovation design, safely reimagine our streets or build partnerships with their communities.

Local leaders who similarly made quick changes at the start of the pandemic and have not evaluated the changes in-depth must now take action to do so. Evaluating the changes is necessary to learn whether residents of various abilities and identities can safely access and enjoy the space and make changes to ensure they do.

The Ideal Scenario: Prioritizing Residents at the Start

Local leaders understandably had to make choices quickly at the start of the pandemic to meet critical needs. By February 2021, almost a year into the pandemic, nearly 60 percent of casual restaurant operators had added outdoor dining, and more than 40 percent of restaurants utilized municipal programs to expand their operations on sidewalks, streets or parking lots. As a result, local leaders can draw on many examples to inspire changes for their own municipalities, retrospectively analyze the ways these changes occurred and ensure equity is incorporated in the planning process in their own communities.

Pop-up Activation Downtown in Bethel, VT

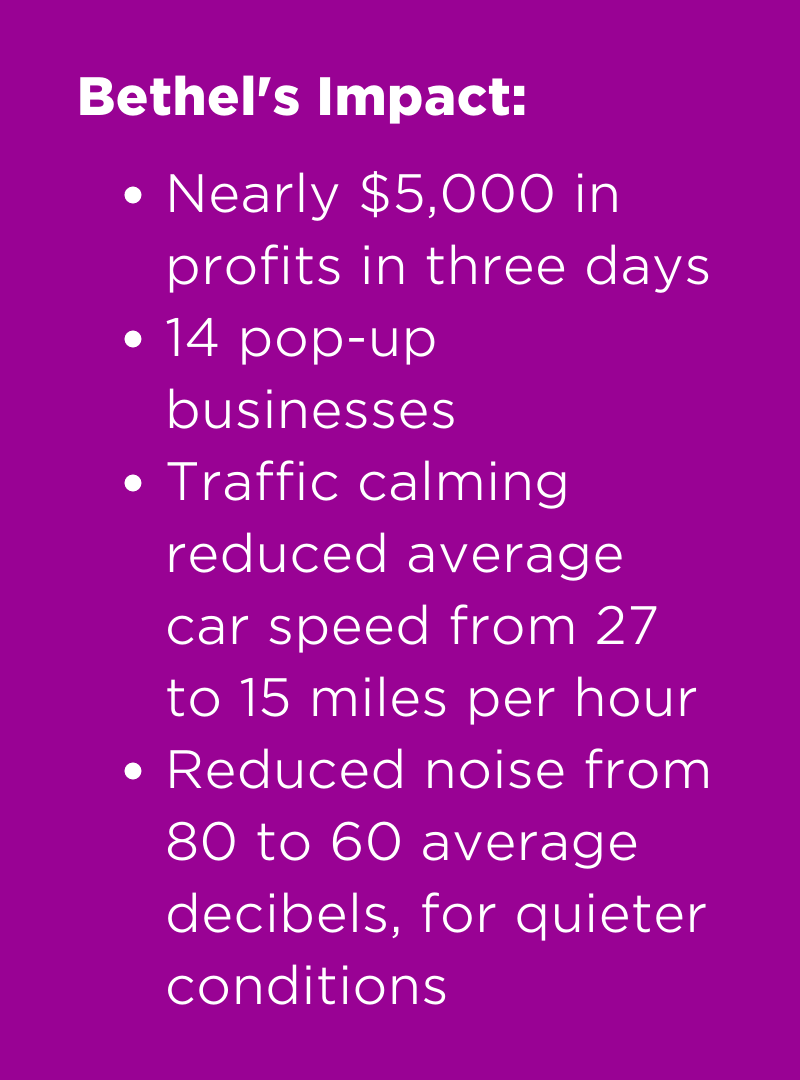

The Town of Bethel’s downtown core struggled for decades to maintain stable businesses after factories moved production, shops closed and retailers chose locations elsewhere. Residents gathered to form the Bethel Revitalization Initiative (BRI) to brainstorm how to reinvigorate the town and place attachment. BRI applied and was selected as a winner of $25,000 from AARP’s Team Better Block technical assistance fund in 2016. The Team Better Block model implements pilot temporary projects over one weekend to see how successful they would be at meeting pre-determined resident goals. BRI, AARP and Team Better Block collaborated to gain more ideas from residents using a variety of methods:

- “Walk and Talk”: The team invited residents to participate in a downtown walking audit to learn about their favorite places, solicit opinions on how some areas might be challenging and collect ideas about where the town could improve.

- Roundtable Conversations with Community Mapping: Residents pinpointed community assets and areas of need on maps of the town.

These activities concluded that preserving town history, maintaining public spaces, implementing safe pedestrian crossings and reducing noise were priorities. Three types of projects were highlighted:

| Project Types | Example Initiatives |

| Traffic Calming, Safety and Streetscape | Crosswalk improvements, transit shelter, parklets, curb bulb-outs, bike lanes |

| Quality of Life & Community Building | Pocket parks, benches, free libraries, public art, outdoor sidewalk games, historic photos, wayfinding |

| Economic Opportunities | Farmer’s markets, pop-up businesses, food vendor stands, outdoor beer gardens, live music |

Team Better Block and AARP of Vermont collaborated to create a video and report that highlighted the initiative’s process and outcomes. The BRI plans to continue hosting similar temporary activation events with the Better Block’s successful model. It has already held a holiday pop-up (making $3,000 in profits) and is planning a summer series of semi-permanent streetscape projects.

Bethel’s successful pop-up events and street calming measures were made possible by residents who took charge of the process. The project is a model to local leaders for how integrating resident values in reimagining public spaces can ensure long-term, successful changes.

Learn More

For more information on how to reimagine public spaces with equity at the forefront, check out NLC’s Future of Cities Reimagining Public Space to Support Main Street Retail municipal action guide.