Edited by Abygail Mangar, NLC Health & Resilience Program Manager.

Although hurricanes and wildfires receive more attention, there is evidence that summer heatwaves harm and kill more people. Extreme heat is responsible for more deaths than all other types of extreme weather events combined, according to the Center for Disease Control. In the Greater Boston area, the number of summer days over 90 degrees has doubled due to climate change. Many residents who live in heavily developed areas still lack air conditioning, heightening their heat risk and also endure mental health risks from heat-induced social isolation. Our people, culture and built environments are not prepared for the major increase in dangerously hot days. The Town of Arlington, a city north of Boston, has a history of prioritizing climate issues at the local level and is working regionally to bring about change in this area.

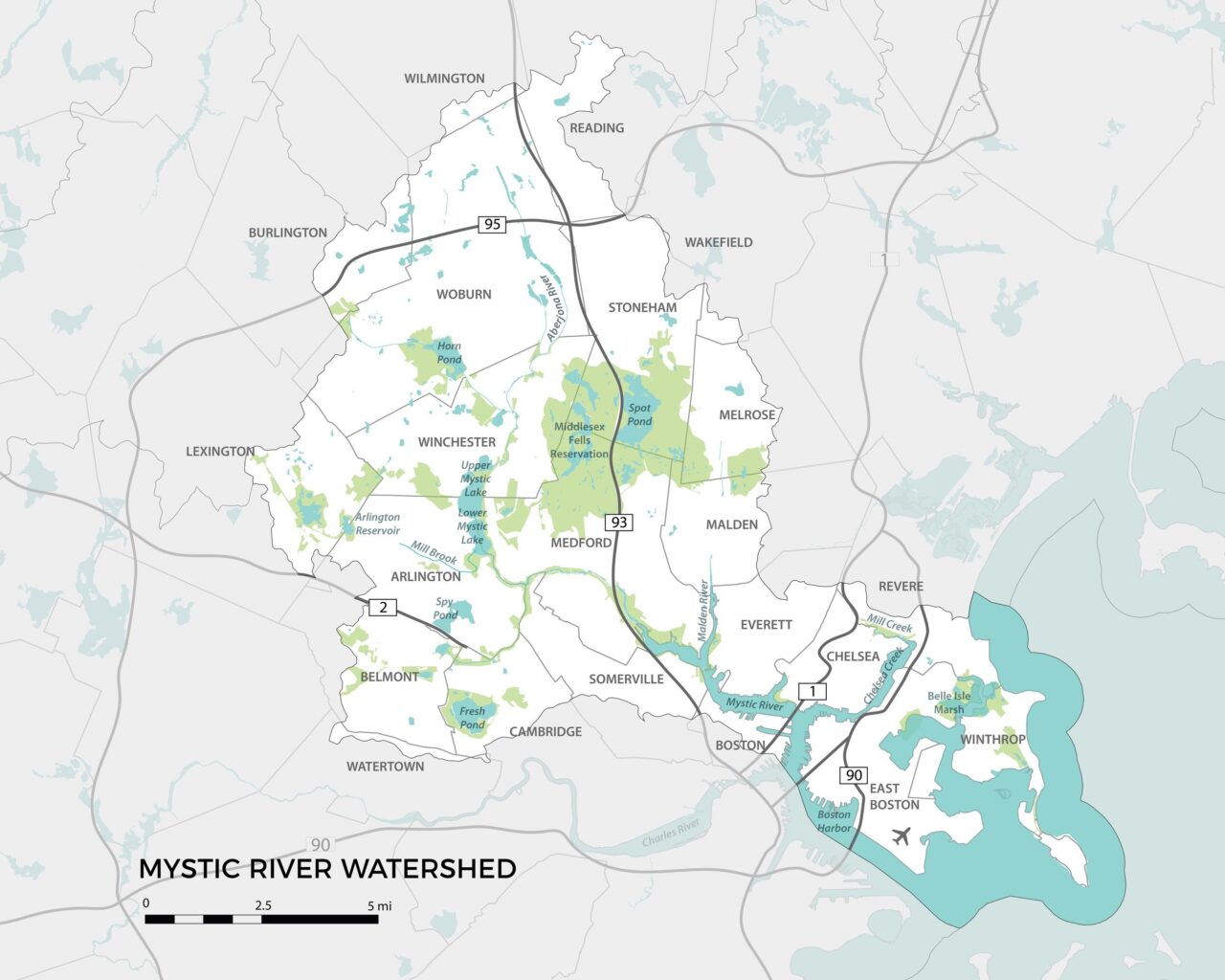

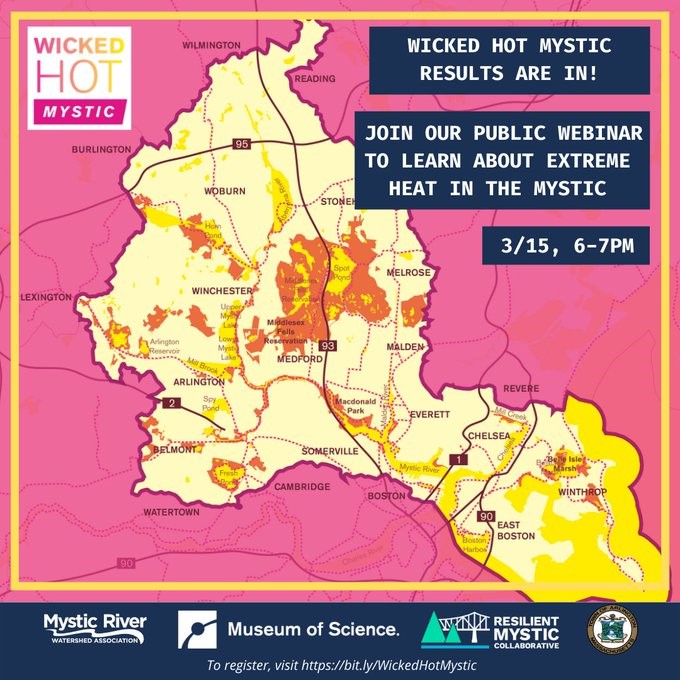

Arlington is one of ten founding municipalities in the Resilient Mystic Collaborative (RMC), a voluntary partnership that has grown to 20 cities and towns working together to protect people and places from extreme weather. The Commonwealth’s Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness (MVP) Program awarded the Town of Arlington a $186,200 grant in September 2020 to develop “Wicked Hot Mystic” watershed-wide maps of the day- and nighttime “real feel” ground-level heat, humidity and air quality. Arlington then received a grant through the National League of Cities’ Leadership in Community Resilience program in 2021 to enable us to work more closely with neighborhoods on community-designed solutions to help people stay cool.

Led by staff from the Town of Arlington and the Mystic River Watershed Association, RMC communities partnered with the Boston Museum of Science, CAPA Strategies and the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) to help identify, prioritize, and mitigate urban heat islands throughout the Mystic River Watershed. We recruited and trained 80 volunteers to drive and bicycle along with specific transits at 6 am, 3 pm, 7 pm, and 6 am the next morning during an August 2021 heatwave. These data points were modeled by CAPA Strategies to create highly granular urban heat island (UHI) maps across 21 communities. This method, developed with Portland State University and the Science Museum of Virginia, has become a standard for measuring ground-level ambient air temperatures.

We now have high-resolution, baseline maps for the entire watershed that correlate high-resolution, ground-level heat and humidity with land use information such as urban tree canopies and distance from water. These maps have proven critical to our regional climate resilience work for several reasons:

- The maps allow municipalities to prioritize investments in the hottest urban heat islands.

- The maps help us allocate our resources equitably, based on the locations of the hottest neighborhoods instead of focusing equally across communities with very different maximum summer temperatures.

- Repeated transects of the same locations will allow us to measure and replicate cost-effective interventions over time to cool priority hot spots (or conversely, document how they are heating up if we are unsuccessful).

As we transition to this next phase of work, the RMC will continue to engage its member cities and towns both regionally and individually. Multiple RMC communities identified extreme heat as a top concern in their MVP plans. Cities and towns in the Lower Mystic River Watershed, including Boston, Cambridge, Chelsea, Everett, Malden, Medford, Revere, Somerville and Winthrop, are heavily developed with few large parks. As such, every Lower Mystic community-identified extreme heat as a priority hazard of concern, especially for its public health risks to vulnerable residents. Upper Mystic communities benefit from more expansive tree canopies and larger open spaces, such as the Middlesex Fells and Mystic Lakes. Nonetheless, Lexington, Melrose, Winchester and Woburn have been harmed by – and continue to recognize – extreme summer heat as an increasing concern for vulnerable residents, energy demands and drought.

For municipalities considering how to address these issues at the local and regional levels, it is important to understand that engaging in these initiatives requires the commitment of local leaders, staff and funding to realize outcomes and participate in outreach and engagement with those impacted by the change. For regional initiatives, strong advocates in nonprofit and regional and state government are critical to maintaining momentum and working together towards transformative change.

The next phase of Wicked Hot Mystic is “Cooling the Wicked Hot Mystic” alongside RMC municipalities, community organizers and interested neighborhoods. Adapting from blizzards to heatwaves will take time, but with local action and regional partnerships, creative solutions are possible to help people stay cool during the Greater Boston area’s rapidly warming summers.

Learn more about NLC’s Leadership in Community Resilience program.

About the Authors:

Jenny Raitt is the Director of Planning and Community Development for the Town of Arlington which includes work on environmental planning, climate resiliency and conservation.

Julie Wormser is Senior Policy Advisor at the Mystic River Watershed Association and co-founder of the Resilient Mystic Collaborative.

Melanie Gárate is the Climate Resilience Manager at the Mystic River Watershed Association where she leads climate resilience task force projects focusing on social inequities, including Wicked Hot Mystic.