We interviewed Lacey Loftin, the data analyst from the Great Lakes Federal Grant Navigation Program (FGNP), an initiative launched by the National League of Cities (NLC) in late 2021. The program assists cities with populations of at least 8,000 in Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Minnesota, Missouri, and Wisconsin apply for additional federal funding.

As applications for grants can be particularly challenging for small and medium-sized municipalities, the Great Lakes FGNP provides grant application support by pairing cities with a grant navigator for coaching and review, a data scientist to conduct a data-driven needs assessment and locally based navigators who offer support during and after the application process.

Additionally, all participating cities of the Great Lakes FGNP are connected to an exclusive communications channel that allows for peer-to-peer connection and information sharing. This specialized resource database promotes collaboration over competition. New grant opportunities, relevant webinars, and other resources are sent directly both by NLC and by other city leaders. The channel provides the space for leaders to directly ask questions, give comments, share resources, and, ultimately, further dialogue between city leaders and NLC.

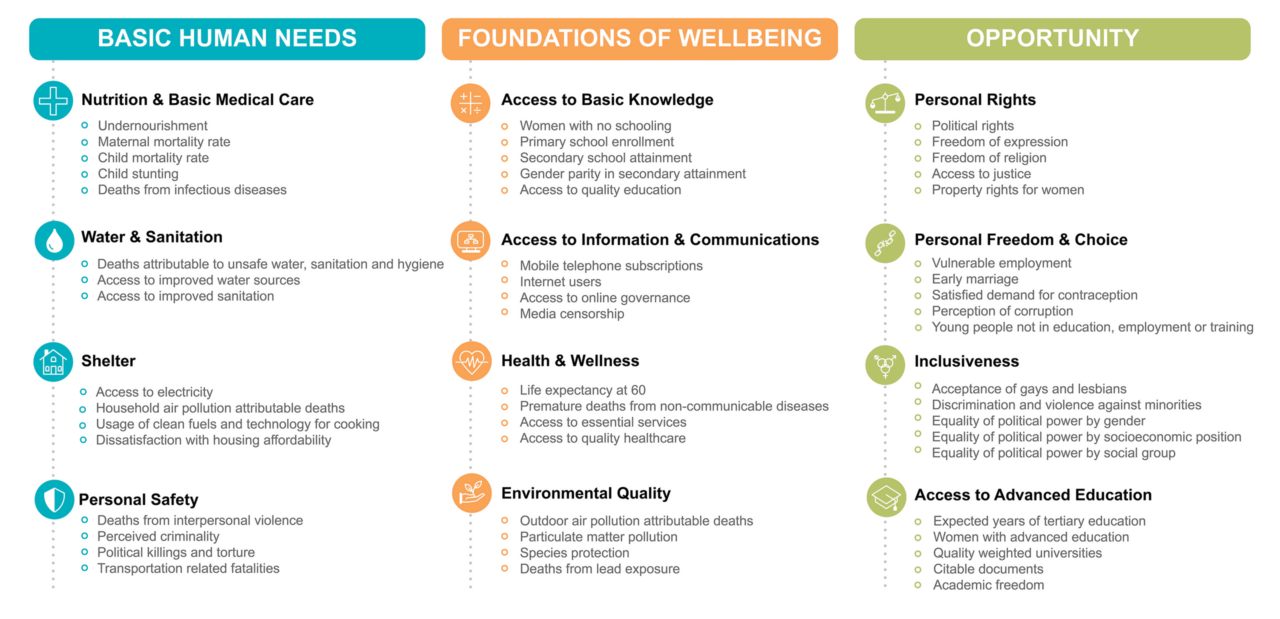

By connecting local leaders directly to resources like data visualization tools, the Great Lakes FGNP facilitates pairing between local priorities and potential funding opportunities. The data visualization tool, made available to participating municipalities, provides leaders with a data-driven approach to conducting a need assessment. It illustrates the measures in which cities have the greatest need while ensuring that local voices stay heard and are centered throughout the process. This unique usage of both qualitative and quantitative approaches becomes an extremely powerful way to create positive community change.

The Great Lakes FGNP process uses the Social Progress Index framework to walk municipal leaders through a needs assessment that best addresses the foundations of community wellbeing, economic opportunity, and human mobility. So far, the program has assisted dozens of cities across the target states in conducting a community needs assessment and creating a data narrative, which will serve as the basis for future federal funding opportunities to ameliorate their communities and respond to pressing issues.

Areas of expressed concern for participating municipalities vary, but the broad categories of water and sewage infrastructure, broadband, housing, and economic development come up consistently.

For example, in conducting a needs assessment for Dumas, Arkansas, it was found that poverty rates are extremely high. Poverty in Dumas is set at 29.9%, which is 15 percentage points higher than the state average. Only 17% of all citizens have a bachelor’s degree or higher, 5 percentage points lower than the state’s average. This is especially true for Female Householders who make up 40.8% of all households. These women experience a 91.3% poverty rate. According to the US Census Bureau, women make up 58.7% of the employed population. However, because women tend to be employed in retail or service occupations, their salaries and overall support are much lower, contributing to the high poverty rate.

Focusing on this demographic has the potential to transform Dumas’ community for the better for generations.

Some communities, like Baton Rouge, Louisiana, have recognized the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 “on health and economic outcomes in low-income areas” affirming the necessity of “building stronger neighborhoods and communities by the development of affordable housing. I have found a need to address the lack of affordable housing to improve health and economic outcomes, by building stronger neighborhoods and thus, communities. 5% of housing stock in Baton Rouge is without plumbing and kitchens. Renter and homeowner burden is estimated to be at about 89% in certain tracts. Baton Rouge applied for federal funding in 2021 and has set aside $6 million to partially fund the Housing for Hero development; a multi-use low- and moderate-income housing development for essential workers and professionals located in a Qualified Census Tract area. The housing project will have 36 units, and 51,000 square feet of mixed-use live and workspace, creating 25 new jobs in the area and providing 1–3-bedroom housing for essential workers and low and moderate professionals.

The needs assessment of Granada, Mississippi, has revealed that its water and sewer pipe infrastructure needs replacement. Incorporated in 1836, this city has infrastructure more than 100 years old. This is especially important as Granada manages the water/sewer infrastructure for the entire county, making it the 5th largest system in the state. At once, a significant population shift has left a public works staff that operates at half capacity, leaving them able to only focus on patching, not long-term fixes. This is also exacerbated by the fact that tax revenue has decreased as a result of a weakened tax base, leaving very little possibility for long-term infrastructure improvements.

These three case studies highlight the differences in regional priorities and how the Great Lakes FGNP utilizes data in supporting those claims. As the categories of infrastructure, broadband, housing, and economic development are seen repeatedly, the Great Lakes FGNP has also hosted webinars like this one that relate specifically to these challenges and specific grant opportunities in these need categories. The Great Lakes FGNP continues to curate content in the form of publications, blogs, and other funding opportunities, shared via the program’s communication channel, available to enrolled cities.

Q+A with Lacey Loftin, data analyst for NLC’s Great Lakes Federal Grant Navigation program:

How do you balance the quantitative side of this work with the qualitative, the more human?

History always precedes the data mostly because the data we have is a point-in-time snapshot of the current situation. Context and history are keys to understanding people, we just didn’t arrive at this precipice, it was decades and sometimes centuries of neglect and denial of human rights that lead us here. To look at just the current state or statistic is to almost certainly resign ourselves to failure. Solutions need to come from a local understanding of HOW we got here and how WE collectively can solve the problem.

Can you briefly walk us through the start to finish process of this work? How/where do you begin looking at the data, where does it usually take you, how do you tease out the narrative, and finally — how do you package that work for leaders?

I begin with a look at US Census Profiles and the SPI Tool to build an understanding of the city and its background. Then, I schedule a call with the city leader and they fill in some more of the gaps for me — city history, for example. They explain their priorities to me and then I pick out several indicators that will point to the state of that priority for the citizens in each tract. For example, there might be a certain number of tracts that have all the markers of poverty, food insecurity, or isolation. From there, it’s a discussion of solutions with city leaders on how to possibly correct the inequalities via the grant opportunity.

What is, in your opinion, the greatest benefit(s) of the Great Lakes FGNP? How have your conversations with city leaders demonstrated this?

One of the greatest benefits is the way in which we deliver the needed management of one of the largest infrastructure grants in human history. It is wholly overwhelming for smaller cities. Almost like being in a wind tunnel full of cash and the most organized/persuasive is the one who wins.

In my wheelhouse, (data), the FGNP has shown me how much municipalities need to have access to their data visualized. To see it laid out in a map as we have it done with the SPI framework really opens up something for the city which they may or may not have known about before or didn’t have access to.

Broadly, where do you see the role of data-driven decision-making in the next year? How do you feel the GLNP will live on?

Data-driven decision-making is the future of governance. No longer will we have to disperse funds to tracts that don’t need it. We can funnel funds and create projects that make the most impact in our cities by using data. By investing in data science we make more of what we have, we make it go further than ever. We make a strategic impact. The FGNP is a vital program that brings the power of grant management and data science to cities and villages that have limited resources. The power of data is that it can take the guesswork out of strategic planning, out of wondering if what we are doing will work or be effective. That is power and confidence.

___________________________________________________________________________________

In conclusion, NLC is delighted to continue connecting and aiding municipal leaders with their grant applications. By using both data and storytelling, the Great Lakes FGNP prioritizes shaping local community needs to meet federal grant requirements. The work that municipal leaders have done thus far to build both for the future and present, speaks to the incredible resilience and insight of these local communities.

The Great Lakes FGNP provides a centralized space to connect directly to NLC and other city leaders, improving collaboration and resource sharing. Further, direct connection to resources like grant navigators that understand both the federal application process and regional needs, and data visualization tools, help cities both understand their local needs and use that to support and strengthen their grant applications.

Learn More

As the program continues, NLC invites cities with populations of about 8,000 in Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Minnesota, Missouri, and Wisconsin to join the FGNP. To learn more about the program and determine if its right for your city or town, please complete the form at the bottom of this page.

About the Authors:

Lacey Loftin, Great Lakes FGNP Data Analyst.

Elizabeth Kostina, former IYEF intern.