Planners, architects and developers have played instrumental roles in how neighborhoods were built and how resources were historically allocated. As tools of privilege and power, professionals in the built environment planning is a tool of privilege and power. For example, Black and Brown-majority neighborhoods were often demolished by new highway systems.

Undesirable systems, such as wastewater treatment plants, were predominantly constructed near or in neighborhoods with majority Black and Brown residents – and not in White-majority neighborhoods where many of the planners lived. The Black- and Brown-majority neighborhoods were also the main neighborhoods demolished to construct the highway systems we see today, as highlighted by Transportation Secretary, Pete Buttigieg. These choices perpetuated the segregation of neighborhoods and the structural racism that was pervasive through policies, including redlining that prevented Black residents from accessing mortgages and home loans.

“There is a gap in representation, a gap in recognition, and a gap in leadership — all of which can impact the way we live our urban lives.” – Katrina Johnston-Zimmerman, Urban Anthropologist (Source: Next City)

Gender in the Public Realm

Women, gender non-conforming people, and people in the LGBTQIA+ community have experienced harassment, discrimination, and violence due to their gender identity and sexuality. Because neighborhoods and communities have been historically designed and constructed by cisgender White men, the experiences of marginalized genders are commonly not properly considered, leading to public spaces that make people feel unsafe or unwelcome.

Health & Well-being in the Public Realm

About 65 percent of women report enduring street harassment, compared to 25 percent of men. Fear in public spaces is a common experience for women, non-conforming genders, and LGBTQIA+. This fear influences the choices of how, when, and where marginalized genders move around in the public realm. These unfortunate experiences hinder how freely they can enjoy public spaces and programming, which can impact their overall mental health and well-being.

Women are more likely to walk or take public transportation than men. This issue is especially worsened by poverty, where wealthier families are more likely to own cars, avoiding public transportation altogether. As most major capital investments have been on roadways, this creates more challenges for women to travel. Dominant roadway investments that further sprawl create more barriers to considering walking, biking, or other non-automotive vehicle mobility. Because the priorities of marginalized genders have not been properly invested in, public transportation systems do not accommodate the needs of people with strollers, people with disabilities, or the lack of connected and safe walkways can put families at risk.

Women report feeling safer in spaces filled with multi-gendered and multi-generational people, demonstrating the importance of designing public spaces that are welcoming to everyone. Working to make these built environments welcoming provides a positive feedback loop: the safer the space is, the more people will use it, and the more willing people are to engage with spaces and bring others to the spaces.

Empowering & Reflecting the Gender Spectrum in Public Space

The designing of a truly inclusive and safe public space must include those impacted in the planning and design process and should not take a “one size fits all” approach to safety.

- Reimagining lighting: Improved lighting increases visibility for drivers and allows people to feel more comfortable walking outside at night, improving both real and perceived safety. Communities can conduct nighttime walking audits to find areas where residents feel the need for additional lighting. Warm lighting promotes relaxation and can decrease light pollution impacts. Some cities considered how to merge artistic design with lighting installations, such as East Boston’s 16 neon lighting structures for an underpass near an East Boston Amtrak station.

- Removing walls: providing clear lines of sight by limiting the number of enclosed spaces where people can become isolated is one way to make the space feel safer. Removing unnecessary walls, or replacing solid walls with translucent walls, can improve safety and make people feel more comfortable walking around at night. Example: 2021 study found women had stronger perceived safety after walls were removed in London, UK.

- Create “Cozy Corners”: cozy corners are spaces with low walls or separations that allow some seclusion without sacrificing public safety. These can make public spaces more welcoming for LGBTQIA+ or people of marginalized genders, as they can enjoy the spaces without as much exposure or eyes on them. An example of a cozy corner is a bench with a planter on three sides of it, proving some privacy without completely blocking off the space.

- Provide necessary amenities: Providing enough public restrooms, including gender-inclusive restrooms, in public spaces can make them more welcoming. For gender non-conforming people, having an accessible gender-neutral restroom can help avoid conflict and unsafe situations.

- Encourage multi-use spaces: Having communities that include businesses, recreation, and residents, improving comfort in spaces. This can improve safety for women and other marginalized genders since they are less likely to be alone or isolated and unable to call for help.

- Provide inclusive programming: Family-friendly and gender-inclusive programming can draw in more marginalized genders and their families to public spaces. Stages, outdoor reading rooms, and recreation facilities can make spaces more welcoming and encourage diverse programming.

- Make spaces visually inclusive: Spaces can foster welcoming feelings for marginalized genders and the LGBTQIA+ community by including art, lighting, and designs made by or representative of the LGBTQIA+ community. This can serve a dual purpose, where rainbow crosswalks, for instance, not only show support for the LGBTQIA+ community but also have been shown to decrease vehicle speeds and improve the safety of pedestrians (SOURCE)

How Local Leaders Can Support Gender Inclusivity in Public Spaces

- Partner with Gender-representative Organizations: when strategizing trusted community groups or local leaders to partner with, ensure you are identifying organizations that represent LGBTQIA+ and women, such as local LGBTQIA+ community centers and women associations (e.g., WTS).

- LGBTQIA+ Data for Development Demographic Analyses: race/ethnicity, gender, age, and socioeconomic income are common demographics reviewed when analyzing an area for development and pinpointing areas of vulnerability. Include LGBTQIA+ data in studies if available to convey truer areas of vulnerability.

- Caucus Groups during the Community Engagement & Empowerment Process: collaboration on designs and built environment decisions should be the number one goal, and in addition, once initial designs are available, host caucus groups for women and LGBTQIA+ to ask their thoughts on the strengths and challenge areas of designs based on their experiences in those places.

- Recruit and Support Women, Non-Conforming Genders, & LGBTQIA+ Overall: about 51 percent of the U.S. population are women and the percentage of LGBTQ adults in the U.S. has doubled over the past decade. Furthermore, 52 percent of urban planning graduates are women. Our workforce and professionals in the design and built environment field must be representative of our population and deserve a seat in the room. Ensure your recruitment and human resources efforts reflect safe and empowering environments.

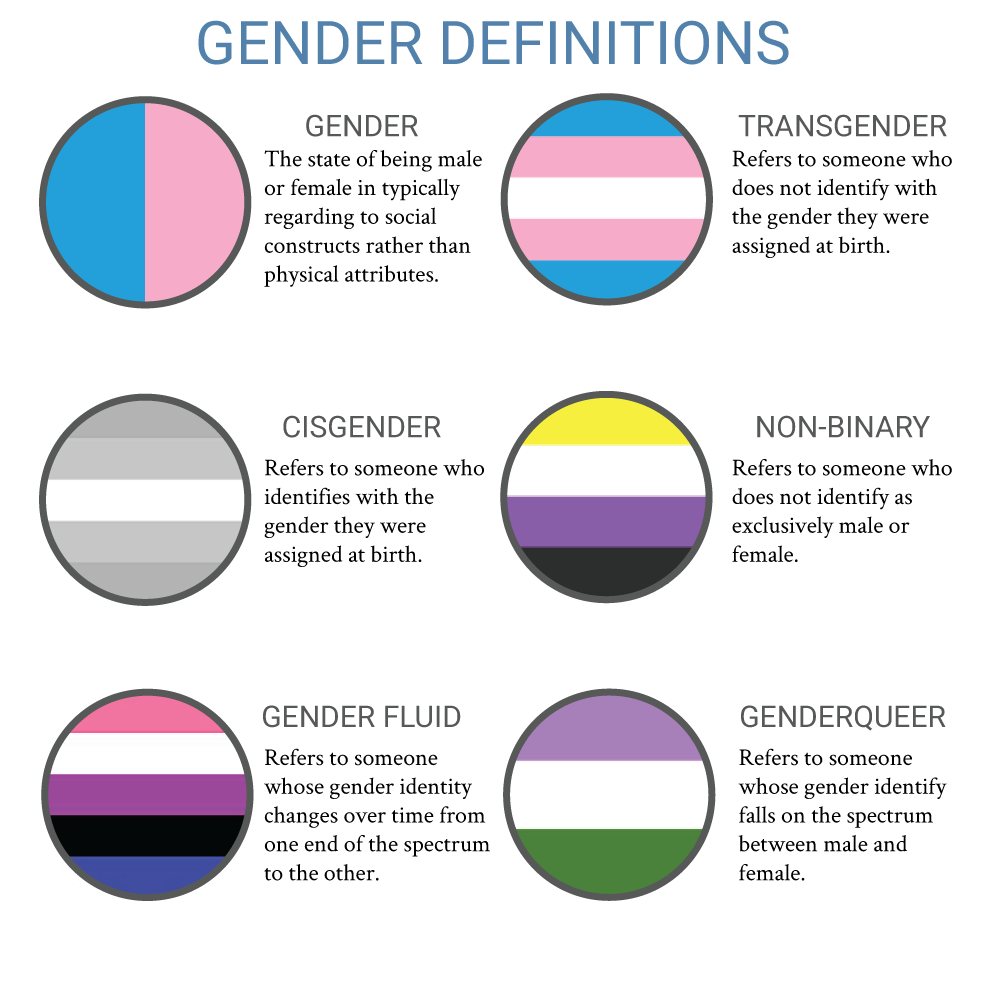

Definitions

- Gender Identity: Defined by HRC as “One’s innermost concept of self as male, female, a blend of both or neither- how individuals perceive themselves and what they call themselves. One’s gender identity can be the same or different from their sex assigned at birth”

- Gender non-conforming: A person whose gender identity does not fit within the traditional binary

- Transgender: A person whose gender identity is different from the gender they were thought to be at birth.