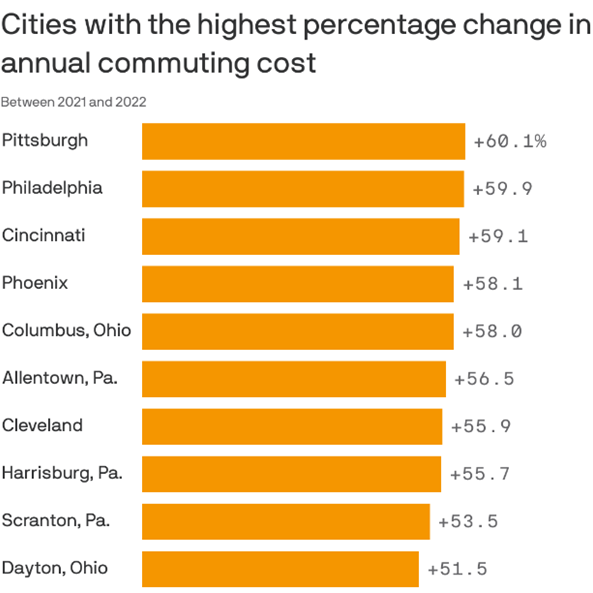

Excess traffic congestion on America’s roadways costs drivers more than $88 billion a year or $1,377 for every driver on the road. These costs come from a combination of factors including loss of time, pollution and safety. In the Twin Cities metropolitan area alone, a Metropolitan Council report estimated the cost of congestion to be $2.6 billion per year or $980 per commuter. This congestion cost is paid in time lost and wasted fuel, as 56 hours or 7 full vacation days are spent in traffic resulting in 18 gallons of wasted fuel. With insurance and gas prices increasing, the cost of commuting is increasing in many cities, with some experiencing more than a 50% increase in commuting costs (See figure 1). But commuters are not the only ones who suffer from congestion and its costs. The American Transportation Research Institute estimates that the freight sector lost $74.1 billion a year due to congestion. This impacts supply chains resulting, in the delay of goods and higher prices.

Adding more lanes along highways and building more roads can’t continue to be the answer. Constructing more lanes on a highway has been shown to have little to no impact on congestion levels. It only leads to induced demand which creates more supply (more lanes) resulting in more drivers which leads to more cars, more air pollution, and the same or potentially more congestion.

In urban areas, adding a new lane of highway per mile costs on average $10 million. The funds to pay for this highway expansion would likely come from the gas tax, the federal, state and local use fee tax used to pay for the expansion and upkeep of roads, which would amount to $60,000 per year on the added lane during rush hours. This amounts to a payoff period of over 166 years for drivers on the road, far longer than any one driver will spend driving in their lifetime. Additionally, as more companies and drivers switch to electric vehicles the gas tax has a dwindling use to fund roads. This dichotomy will also lead to inequitable outcomes as electric vehicle owners, who tend to be wealthy, will be using the roadways without paying for them through the gas tax.

Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Programs

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) presents unique opportunities for municipalities and their partners to seek innovative solutions to address both traffic congestion and the long-term issues with the gas tax to fund infrastructure. These programs are:

- Congestion Relief Program

- Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program

- Motor Vehicle Per-Mile User Fee Pilot Program

Congestion Relief Program

The Congestion Relief Program is a new program available to municipalities and MPOs in urbanized areas with a population of more than 1 million. States may also apply or be brought in as a partner. This competitive grant provides funds for the design, implementation, and construction of projects that aim to reduce congestion and related economic and environmental costs. Examples of eligible projects include:

- Deployment and operation of mobility services

- Integrated congestion management systems

- High occupancy vehicle toll lanes

- Cordon pricing

- Parking pricing

- Congestion pricing

- Incentive programs that encourage users to carpool or use non-highway travel modes

Priority will be given to projects in urbanized areas that experience high degrees of recurrent congestion, and applicants must consider and include mitigation measures for the potential effects of the project on low-income drivers. The Congestion Relief Program has allocated $250 million over four years. Each grant award will be no less than $10 million, with a minimum 20% non-federal matching share.

Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program

This Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program (CMAQ) provides funding for areas that currently do not meet (nonattainment areas) or previously did not attain (maintenance areas) the National Ambient Air Quality Standards for ozone, carbon monoxide, or particulate matter. The EPA Green Book can be used to determine if your community is a nonattainment area for various pollutants under the Clean Air Act. Proposed projects should reduce congestion and mobile source emissions in the designated area. Examples of projects that were eligible under previous and current versions of CMAQ include:

- Congestion reduction and traffic flow improvements

- Travel demand management

- Transit improvements

- Freight and intermodal

- Innovative projects

- Bicycle and pedestrian facilities and programs

- Car sharing

CMAQ has expanded eligibility through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Funds can now be used for:

- Shared micromobility, including shared bike and scooter systems

- Purchase of diesel replacements or medium/heavy duty zero emissions vehicles and related charging equipment

- Modernization/rehabilitation of a lock and dam or a marine highway corridor, connector, or crossing if it connects to a highway system, likely contributes to air quality and represents less than 10% of the total project cost

This grant requires the prioritization of disadvantaged communities or low-income populations when the funds are used to reduce PM2.5 emissions.

Most program features are the same as the previous CMAQ program that was under the FAST Act. Two new features from BIL are assistance to MPOs and operating assistance. MPOs serving an area with a population of more than 1 million can request assistance from the Department of Transportation to track progress made in minority or low-income populations as part of a performance plan. CMAQ funds can also be used for operating assistance for transit systems located in certain areas.

Motor Vehicle Per-Mile User Fee Pilot Program

As revenue from the existing state and federal gas tax continues to decline, federal, state and local governments are considering congestion pricing or per-mile user fees as a funding solution. Per-mile road usage fees are being considered to replace the gas tax, and charge drivers a fee based on the number of miles driven. BIL directs the Department of Transportation to create a national per-mile road usage fee pilot program while continuing to support state-led pilot programs. The nationwide pilot program will include volunteer participants and both commercial and passenger vehicles, providing different methods for tracking mileage. Local leaders can play a key role in advocating that their state and region participate in these pilot programs, giving local voice and action to the projects.

The Surface Transportation System Funding Alternatives Program (STSFA), the predecessor to this new pilot program, funded 13 state-level pilot programs aimed at testing the feasibility of per-mile user fee systems in states and regionals. The main challenges that arose from these pilots, which will be further studied in the nationwide pilot, were concerns about the privacy of participants, equity concerns, and administrative costs from starting up a new system.

Solutions Cities and their Partners are Using Today

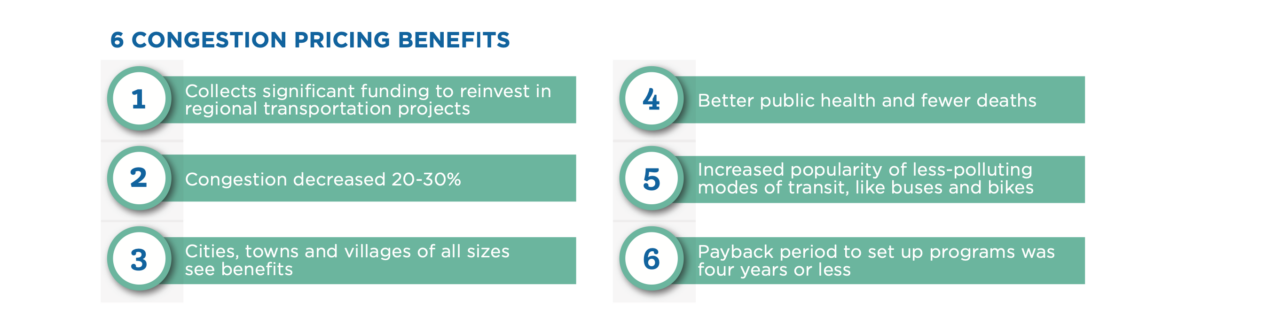

In 2019, NLC wrote Making Space: Congestion Pricing in Citieswhich looked at how London, England, Stockholm, Sweden, and Singapore are utilizing a congestion charge. The report also looked at congestion and public transportation data in U.S. cities, explored equity considerations and recommended that small- and medium-sized cities remain open to the idea of congestion pricing as places like Durham, England, (pop. 33,780) and Znojmo, Czech Republic, (pop. 33,780) have introduced a congestion charge in certain areas of their cities.

Cities and their regional partners are also experimenting with high-occupancy toll lanes to reduce congestion at peak times. San Diego, CA, Minneapolis, MN, Salt Lake City, UT, Denver, CO, Houston, TX, and Northern Virginia are all using some form of demand pricing on their area highways.

States are considering both congestion pricing and per mile user fees to reduce congestion and fund transportation projects. Virginia has implemented dynamic high-occupancy toll lanes that charge vehicles with one or two passengers a different toll rate based on traffic conditions, encouraging people to carpool or drive at off-peak times. Utah, one of the states in the per mile user fee pilot program under STSFA, has drivers pay a per mile charge of 1.52 cents per mile. People with electric, plug-in hybrid or gas hybrid vehicles can volunteer for the program in place of their annual registration fees. The program is designed so volunteers can pay less than their registration fee if they drive less but will not have to pay more if they drive more. This encourages people to drive less while providing a stable funding source for projects and ensuring that all vehicle owners pay their fair share for driving.

How Do You Know if a Congestion Charge is Right for your City?

Local leaders can begin by looking at the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) Urban Congestion Reports to see how their congestion has changed over time and how it compares to peer metro areas. Each report is based on quarterly data and compares the three months of the quarter to the previous year. The dataset currently includes 53 urban areas in the U.S.

The Eno Center for Transportation also has an informative guide on the three stages of ideation, planning and strategy in developing a congestion pricing program with equity and sustainability in mind. The guide is designed for local leaders as they try to address the institutional and communication barriers in trying to establish a congestion pricing program.

Thinking about congestion pricing and long-term ways to fund infrastructure and reduce traffic and carbon emissions should not just be reserved for big cities. Surrounding cities and towns, suburbs, and MPOs have a role to play in establishing partnerships to work together to find the right solutions for their region. Both issues, congestion and long-term funding can’t just be solved by core-downtown cities. These regional coalitions are critical in getting state governments to support long-term funding solutions to infrastructure. Lastly, cities, towns and villages that may not be ready for congestion pricing but want to reduce congestion or their carbon footprint should look at other BIL programs such as Rebuilding America Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) or the Carbon Reduction Program. Municipal leaders interested in congestion issues should begin by looking at data in their own community, meet with stakeholders to think about a solution for their region and continue to check BUILD.gov for updates on the BIL program mentioned above.