The American Rescue Plan Act’s (ARPA’s) State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program has been integral in meeting the needs of America’s cities, towns and villages in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2020, projections showed that a long and deep recession similar to (if not worse than) the Great Recession of 2008 would impact the national economy. State and local governments were concerned they would not be able to weather the economic shock of the pandemic on their own, especially if they wanted to avoid the multi-year budget struggles they experienced after the collapse of the global economy in 2008.

With the implementation of the SLFRF program, municipal budgets stabilized during a time of great uncertainty and local governments could maintain consistent spending for normal government operations and services with minimal interruption, even as they addressed the unanticipated demands of the pandemic. The flexibility of these funds to address municipal and resident needs was critical to the program’s success in stabilizing local government budgets. The Treasury’s revenue replacement option allowed local governments of all sizes to determine the pandemic’s impact on individual municipal budgets and encouraged innovation to address the new challenges posed by the pandemic.

As of the April 2023 reporting deadline, NLC research found that over 96 percent of municipalities that have reported had budgeted some of their SLFRF dollars using Treasury’s revenue replacement expenditure category, though only 4 percent budgeted all their funds for revenue replacement. For further insight into the revenue replacement expenditures of larger SLFRF recipients, review NLC, Brookings Metro, and the National Association of Counties’ (NACo) joint-Local Government ARPA Investment Tracker and corresponding blogs.

Within the Government Operations spending group, Tier 1 cities and consolidated cities have obligated:

- 70% of Government Operations funds to Fiscal Health Recovery

- Examples: stabilizing and supporting municipal budgets throughout the pandemic.

- 19% of Government Operations funds to Government Employee Wages and Hiring

- Examples: hiring or funding public sector staff, providing incentives and bonuses for public sector staff that worked throughout the pandemic, etc.

- 8% of Government Operations funds to Other Government Investment

- Examples: hiring consultants to manage ARPA fund reporting, minimizing court back logs throughout the pandemic, etc.

- 3% of Government Operations funds to Investments in Government Facilities, Equipment and IT

- Examples: updating software for local government departments, increasing cleaning of public government spaces throughout the pandemic, supplying equipment for remote work throughout the pandemic, upgrading government HVAC systems, etc.

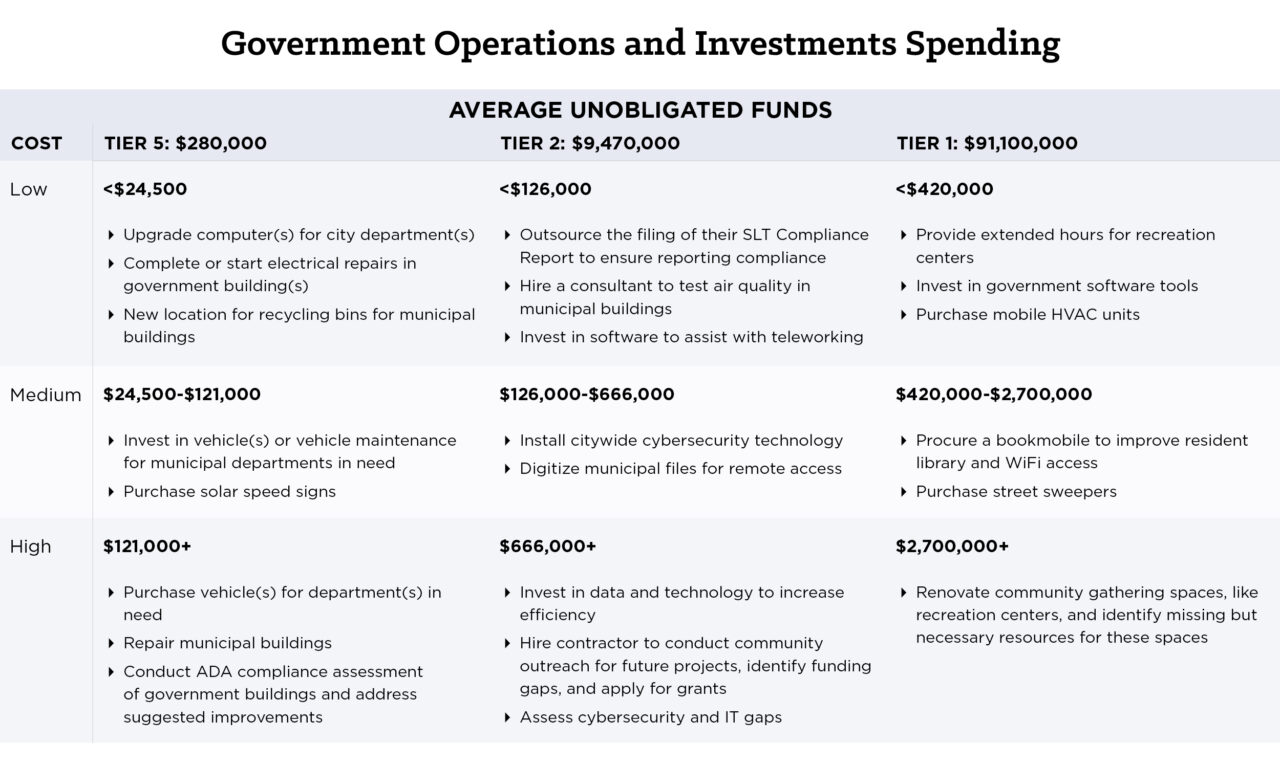

Although the above data represents the spending pattern of the largest cities in the US, localities of all sizes have made meaningful investments using SLFRF to stabilize municipal budgets, address public sector hiring needs and upgrade internal systems to improve municipal service delivery. This blog highlights spending ideas for how to meet the 2024 obligations deadline; however, be sure to review Treasury’s Final Rule for compliance and reporting guidance before considering the implementation of the use cases below.

Spending Opportunities

The following Spending Category Matrix presents multiple examples for different categories of spending (low, medium, and high cost) that can be utilized by governments of various tiers in obligating their remaining funds. The Government Operations spending category was developed in partnership with NLC, Brookings Metro, and NACo for the Local Government ARPA Investment Tracker. This resource is another tool for local leaders to find thousands of project ideas across tiers.

Local Spotlights

- Pinehurst, NC allocated around $234 million to support municipal information technology services, including covering overtime salaries for municipal IT staff, maintaining municipal software programs and managing a secure network infrastructure.

- Kansas City, KS used $35,000 to acquire a customizable online grants management system accessible to community partners for grantmaking.

- Reno, NV allocated $11,000 to purchase a speech-generating service to enhance communication and customer service with constituents and city staffers and create a welcoming and inclusive environment for anyone with speech impairments.

After ARPA – A Call for Continued Federal Support

In conclusion, ARPA has been a lifeline for many municipal governments that faced unprecedented challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, as the SLFRF obligation period is set to expire by the end of 2024, local leaders can plan ahead and explore other sources of revenue to sustain their vital programs and services. Some possible avenues include partnering with the private sector, applying for grants from foundations and nonprofits, and leveraging local taxes and fees.

However, these options may not be enough to meet our communities’ growing needs and demands. Continued support and investments in local governments beyond ARPA can ensure that local leaders have the resources and flexibility they need to thrive in the post-pandemic era.

Glossary

- American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) is the $1.9 trillion economic stimulus and pandemic recovery legislation signed into law by President Joe Biden on March 11, 2021. This blog and its series focus on the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program; therefore, authors may use “ARPA” and “SLFRF” interchangeably.

- Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) is the $350 billion program authorized by ARPA that provides economic stimulus and pandemic recovery funding to U.S. states, territories, cities, counties, and tribal governments.

- Allocations are the total funds distributed to state and local governments through SLFRF.

- Adopted Budget is dollars distributed to local governments through SLFRF that have been budgeted or committed to specific initiatives or programs.

- Spent means the grantee has issued checks, disbursed cash, or made electronic transfers to liquidate (or settle) an obligation.

- Obligations are dollars distributed to state and local governments through SLFRF that have been legally dedicated to specific uses, frequently (but not exclusively) through contractual agreements. The Treasury’s recent guidance defines obligations as “orders placed for property and services and entry into contracts, subawards, and similar transactions that require payment.” The Final Rule requires recipient local governments to obligate 100 percent of their SLFRF allocations by December 2024.

- Tier 1 local governments are metropolitan cities and counties with populations greater than 250,000. These jurisdictions include states, U.S. territories, and counties but NLC’s focus for this series is on cities. These governments are required to report quarterly, and the last reporting date captured in our data is from September 30, 2023.

- Tier 2 local governments are metropolitan cities with a population below 250,000 residents that are allocated more than $10 million in SLFRF funding, and NEUs that are allocated more than $10 million in SLFRF funding. These jurisdictions include counties but NLC’s focus for this series is on cities. These governments are required to report quarterly, and the last reporting date captured in our data is from September 30, 2023.

- Tier 5 local governments are metropolitan cities with a population below 250,000 residents that are allocated less than $10 million in SLFRF funding, and NEUs that are allocated less than $10 million in SLFRF funding. These jurisdictions include counties but NLC’s focus for this series is on cities. These governments are required to report yearly, and the last reporting date captured in our data is from April 31, 2023.

- Non-entitlement units (NEUs) are local governments that typically serve 50,000 residents or less. Of the $65.1 billion allocated to municipal governments across the country, SLFRF allocated $19.5 billion, or 30 percent, to NEUs. Comparatively, SLFRF allocated $45.6 billion, or 70 percent, to metropolitan cities. Depending on if an NEU is a Tier 2 or Tier 5 recipient, they may have different reporting requirements.

Acknowledgments: Thank you to Christy Baker-Smith, Irma Esparza Diggs, Josh Franzel, Michael Gleeson, Patrick Rochford, Archana Sridhar and Melissa Williams for their support and review of this blog.