Co-authored by Glencora Haskins and Mayu Takeuchi

This month marks the third anniversary of the passage of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) and its $350 billion Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program, administered by the U.S. Department of the Treasury. State, local, and tribal governments have had three years to appropriate, obligate and spend SLFRF dollars to address the health, economic and fiscal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since the SLFRF program’s inception, Brookings Metro, the National League of Cities (NLC), and the National Association of Counties (NACo) have monitored how the nation’s largest cities and counties (those with populations greater than 250,000) have used their $65 billion share of these funds through the Local Government ARPA Investment Tracker. This update provides new insights into how large local governments have used SLFRF dollars over the past three years to foster an equitable economic recovery from COVID-19 and their progress to date in obligating these funds in time for the Treasury’s impending December 2024 deadline. As of ARPA’s three-year anniversary, all SLFRF recipients have just over nine months left to meet this deadline before they will be required to return any unobligated funding to the Treasury.

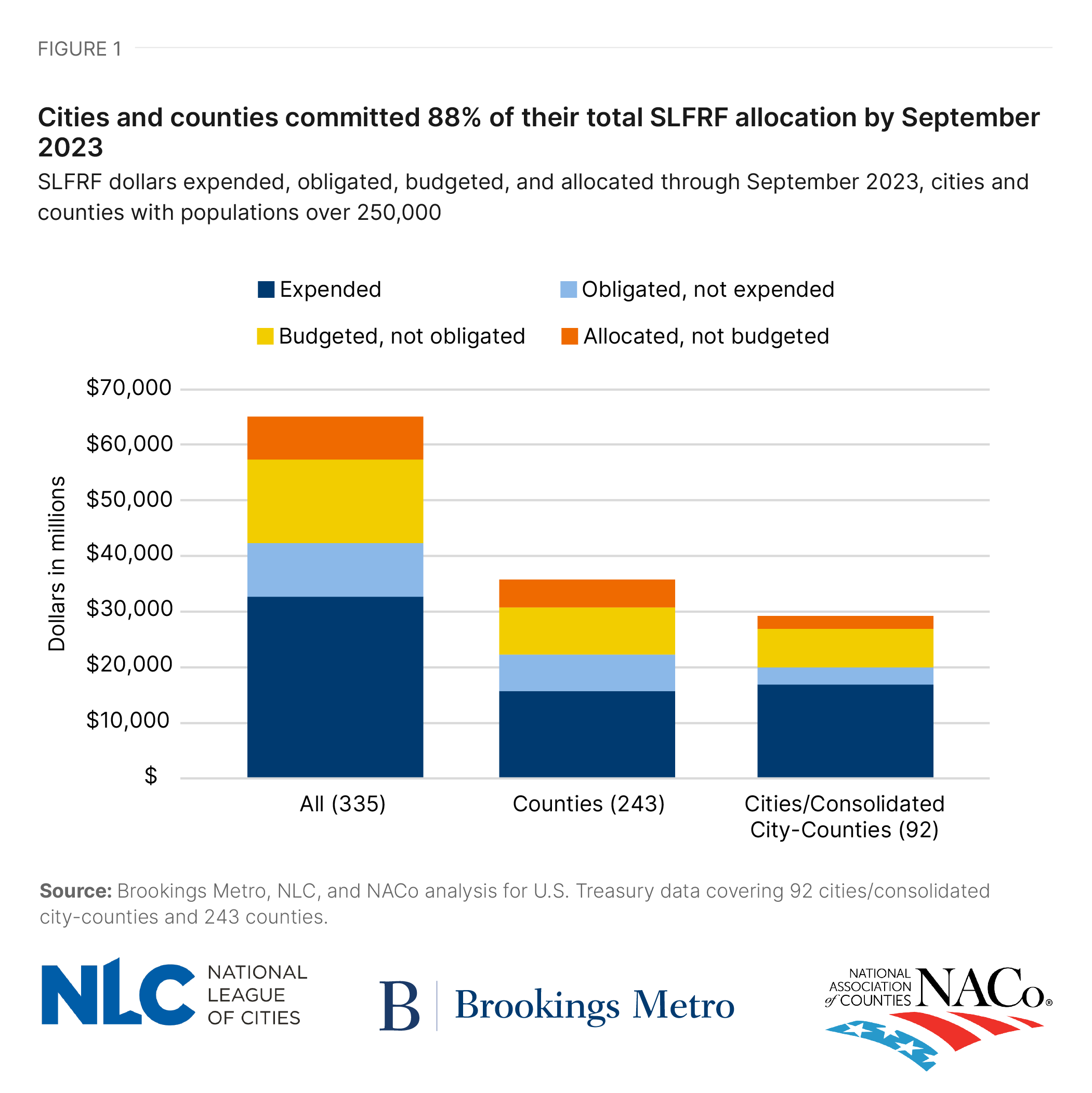

Large Cities and Counties Have Committed 88% of Their Total Allocation as of September 2023

As of September 30, 2023, 335 large cities and counties have reported their appropriations, obligations and expenditures for a total of 14,186 projects—a 7% increase from the previous reporting period. (For definitions of these terms, see the Glossary at the end of this piece). The total number of projects underway in these large local governments has continued to grow, however, appropriations only increased by 3 percentage points between June 2023 (85%) and September 2023 (88%).

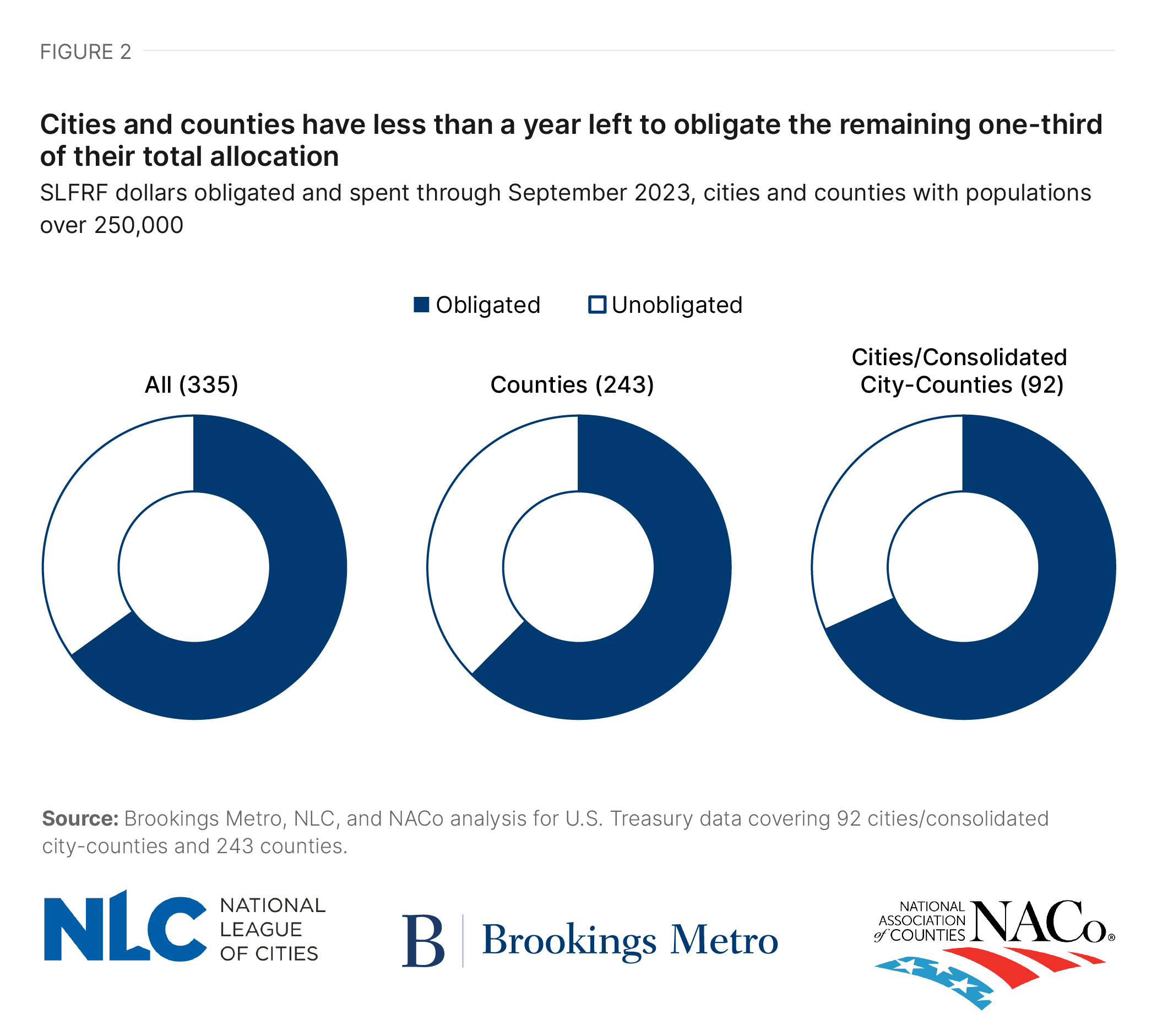

Three years into ARPA, it is becoming increasingly important to also focus on the amount of funding that cities and counties have obligated to specific projects, as Treasury requires that all SLFRF allocations must be obligated by the end of December 2024. Large cities and counties have so far obligated approximately two-thirds of their allocation (65%). In total, $22.8 billion remains unobligated.

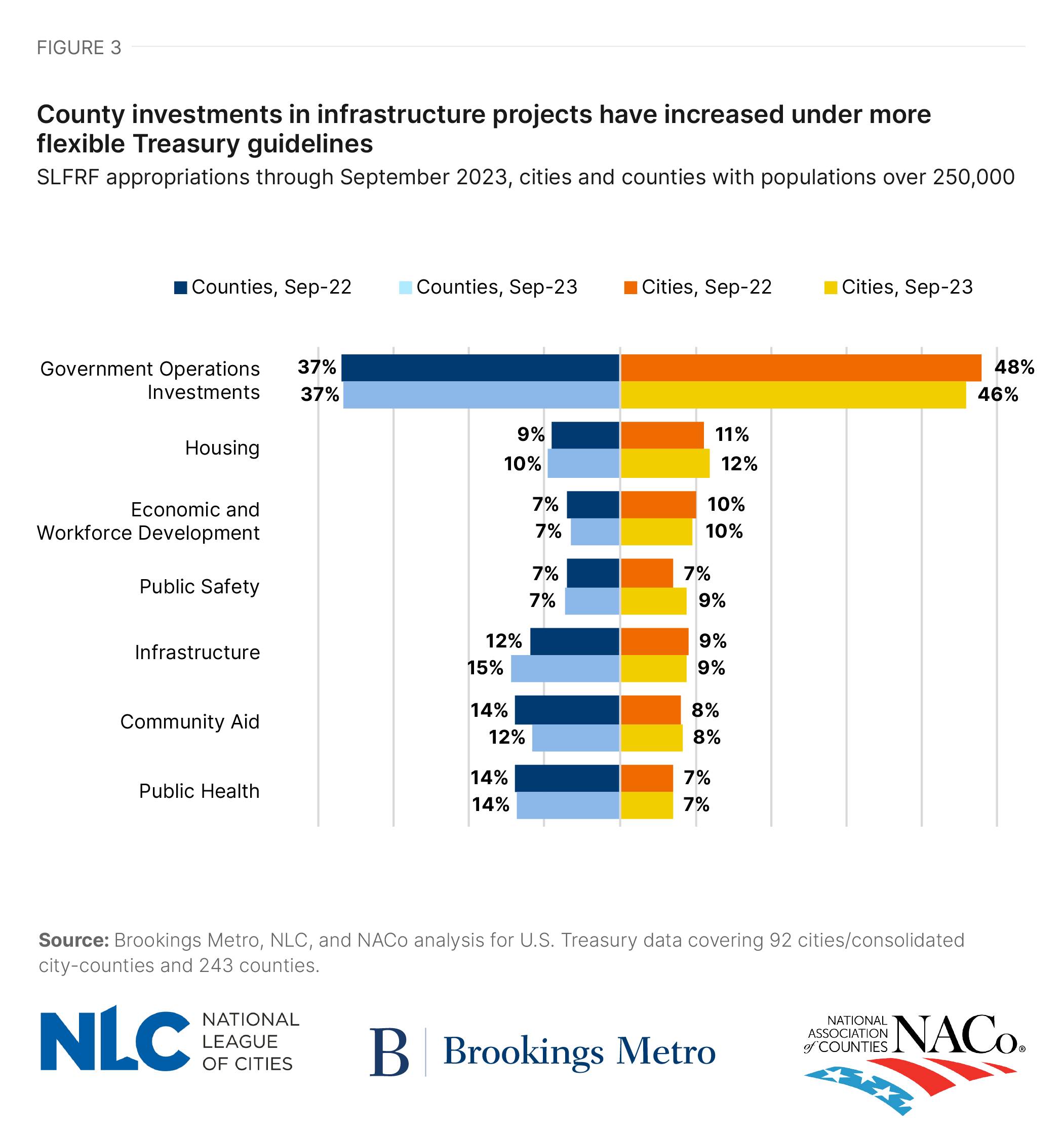

Government Operations Account for the Largest SLFRF Allocations in Large Cities and Counties, with Large Counties Increasing Their Infrastructure Allocations Over the Past Year

Investment priorities for large cities and counties have remained largely stable over the past year. As with past updates to the Tracker, government operations accounted for the largest share of investment in large cities (46%) and counties (37%). Yet large counties have posted a noticeable increase in the share of their appropriations dedicated to infrastructure investments. This is potentially a result of new Treasury guidelines affording cities and counties greater flexibility to use SLFRF dollars for infrastructure and disaster relief. Cities, meanwhile, have increased the amount of funding committed to public safety investments—a possible response to pandemic-era increases in crime (though these trends have largely been declining since 2020).

Unpacking Revenue Replacement: What is the Revenue Loss Prevention?

As the deadline for obligating SLFRF dollars grows near, local decisionmakers, media outlets and community members have intensified their attention on the program’s revenue loss provision. This revenue loss provision introduced a “revenue replacement” classification that includes far fewer restrictions on how SLFRF dollars can be spent. All SLFRF recipients can classify at least $10 million of their allocations in this way or use a formula the Treasury provides to calculate their actual revenue lost as a result of the pandemic to classify a larger amount.

Cities and counties gain significant advantages from categorizing their funding as revenue replacement. First, fiscal stability: State and local governments lost at least $117 billion in expected revenue in the early days of the pandemic. The revenue replacement provision has prevented public sector layoffs and furloughs, maintained critical government services and kept public coffers whole. Second, less administrative burden: The flexibilities the revenue loss provision affords are much-needed for small local governments, for which creating comprehensive compliance and reporting systems was unrealistic while dealing with the COVID-19 emergency. Therefore, reducing the burden of federal program compliance in these areas allowed the Treasury to make the SLFRF program implementable for even the smallest local governments.

How Can Local Governments Balance Speed, Efficiency and Transparency?

The previous section outlines many of the advantages of revenue replacement for local governments. However, one disadvantage is that it is sometimes hard for Treasury, local stakeholders and the public to track what happens to SLFRF resources after they are categorized as revenue replacement. Indeed, the Treasury intended that the SLFRF program be used to “support a truly equitable recovery and address health and economic disparities, exacerbated by the pandemic, in the most underserved communities.” By allowing greater flexibility to local governments, they may deviate from this stated purpose.

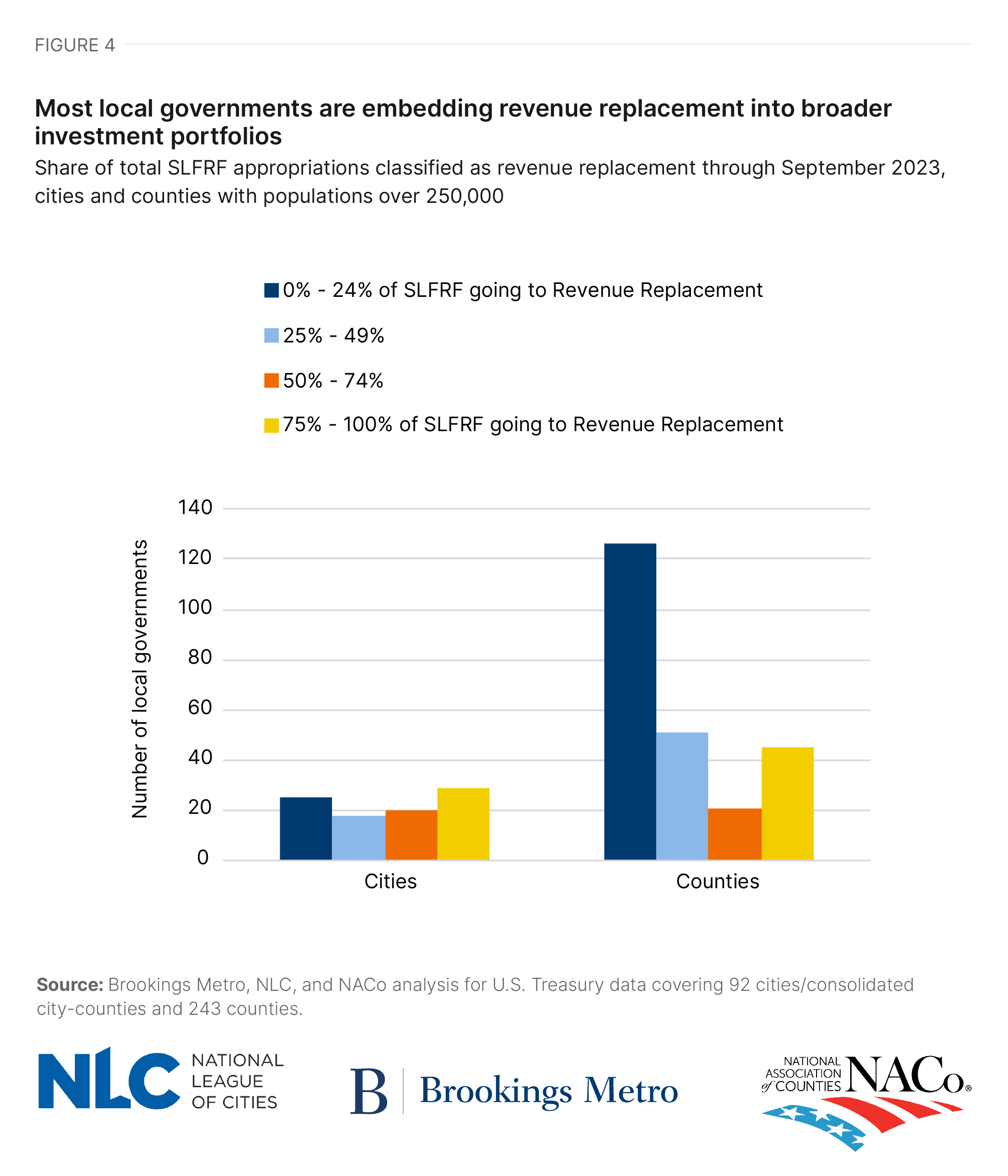

While most large cities and counties are taking advantage of the revenue loss provision to some degree, relatively few are using it to exempt their entire allocation. As of September 2023, two-thirds of large local governments had classified less than half of their appropriations as revenue replacement, including the 13% that did not use the revenue loss provision for any of their appropriations at all. Only 11% of large cities and counties have classified 100% of their SLFRF allocation as revenue replacement.

Consistent with prior Brookings research, the vast majority of appropriations that large local governments have classified as revenue replacement have officially gone to government operations ($18.7 billion). Approximately 75% of these revenue replacement investments in government operations are further classified in our Local Government ARPA Investment Tracker as “Fiscal Health Recovery”—a category typically reserved for large lump sum deposits into city and county general funds with little detail about how the funds will be used. Yet even when local governments provide more detail for how they are spending these funds, the flexibility of the revenue loss provision makes it difficult to tell what types of projects were truly ARPA-enabled. For example, a large city or county may officially spend ARPA funds classified as revenue replacement on expenses typically supported by general fund revenue, such as public sector wages. This, in turn, frees up general fund resources for other ARPA-enabled investments, but the jurisdiction does not report such indirect investments to the Treasury. Local governments can benefit from the flexibility revenue replacement affords while still committing to financial transparency and community awareness. Examples of local governments that have condensed their federal reporting in this way without limiting their community-level impact-tracking efforts include:

- Kalamazoo County, Mich., which reported 100% of its appropriations through September 2023 as a single, $51.5 million revenue replacement project described as covering “a myriad of internal county department projects as well as community partner projects.” However, the county separately maintains a public-facing ARPA dashboard that clearly communicates its total appropriations, obligations, and expenditures through the most recent Treasury reporting period; breaks down these appropriations by each of the county’s six strategic recovery priorities; and provides detailed award data for all of the county’s 79 sub-projects that ARPA funds. The website also links directly to the county’s federal performance reports and ARPA-related financial documentation.

- Greensboro, N.C., which reported 100% of its appropriations through September 2023 as two general fiscal health recovery projects classified as revenue replacement. The city also maintains a website providing comprehensive, up-to-date information about how it is using its SLFRF allocation (broken down across the city’s three strategic recovery priorities) and a status tracker for the amount of funding the city has appropriated, obligated, and spent. The website additionally links to detailed funding authorizations and program descriptions of all council-approved projects the SLFRF program has enabled.

As Treasury’s Obligation Deadline Grows Nearer, Project Portfolios May Need to Evolve

With less than a year left until the December 2024 deadline, more than one-third of the funding allocated to large local governments remains unobligated. Treasury’s recent guidance has opened a new, more flexible revenue replacement classification to help local governments meet this deadline. As local leaders continue to seek ways to use their allocations to promote an equitable economic recovery in their communities, they should look to their peers for ideas on how to ensure that all of their funding is obligated before the December deadline, while also prioritizing community-level transparency, awareness, and financial accountability.

Glossary

Allocations are the total funds distributed to state and local governments through the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program.

American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) is the $1.9 trillion economic stimulus and pandemic recovery legislation signed into law by President Joe Biden on March 11, 2021. This legislation is also referred to as the “American Rescue Plan” or “ARPA.” This piece focuses solely on the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program, and thus, “ARPA” and “SLFRF” are used interchangeably.

Appropriations are dollars distributed to state and local governments through the SLFRF program that have been budgeted or committed to specific initiatives or programs. In this piece, “appropriations,” “investments,” and “commitments” are used interchangeably.

Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) is the $350 billion program authorized by the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) that provides economic stimulus and pandemic recovery funding to U.S. states, territories, cities, counties, and tribal governments. This piece focuses solely on the SLFRF program, and thus, “ARPA” and “SLFRF” are used interchangeably.

Obligations are dollars distributed to state and local governments through the SLFRF program that have been legally dedicated to specific uses—frequently (but not exclusively) through contractual agreements. The Treasury Department’s newest guidance defines obligations as “orders placed for property and services and entry into contracts, subawards, and similar transactions that require payment.” Treasury requires recipient cities and counties to obligate 100% of their SLFRF allocations by December 2024.

Revenue Loss is an SLFRF provision that allows local governments to classify some or all of their allocations as “revenue replacement.” Local governments may claim up to $10 million as “revenue replacement” as a standard allowance without any requirement to demonstrate a loss of revenue, or more if they are able to demonstrate a loss of revenue attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Revenue Replacement is an eligible use classification established in the SLFRF program. Funds classified as “revenue replacement” through the SLFRF program’s revenue loss provision can be used for any government service permissible under state law and are not subject to many SLFRF programmatic reporting requirements.

Tier 1 Local Governments are metropolitan cities and counties with populations greater than 250,000. These jurisdictions are also referred to as “large local governments” or “large cities and counties.”

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Alan Berube, Joseph Parilla, Teryn Zmuda, Christine Baker-Smith and Ricardo Aguilar for research advice and support.