Co-authored by Glencora Haskins, Senior Research Analyst and Applied Research Manager, Brookings

Mayu Takeuchi, Research Assistant, Brookings

Joseph Parilla, Senior Fellow & Director of Applied Research, Brookings Metro

Housing affordability remains a central concern for U.S. households. Even as inflation has cooled, interest rates and home borrowing costs have remained high, putting homeownership out of reach for more people and leaving them in an increasingly unaffordable rental market. Surveys have repeatedly demonstrated that American households cite the housing market as a pain point in an economy where most indicators are trending positively.

One important—but perhaps overlooked—source of investment in affordable housing designed to alleviate these pressures has been the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program, part of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), which provided flexible funding to localities and states to support economic recovery. With housing becoming a critical election-year issue, this analysis assesses how the nation’s largest cities and counties (those with populations greater than 250,000) have used SLFRF funds to invest in affordable housing development, rental assistance, and eviction prevention programs.

About the Local Government ARPA Investment Tracker

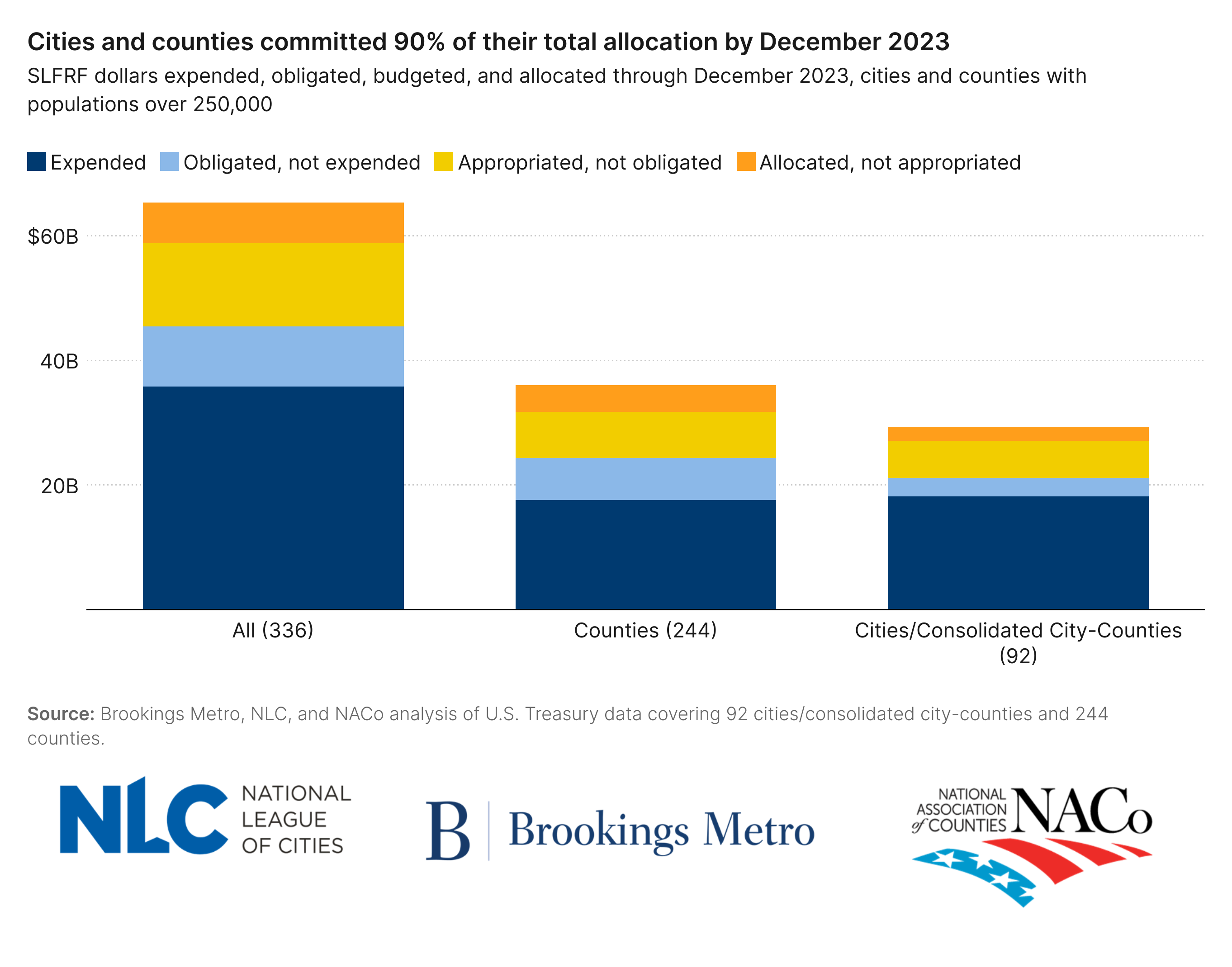

This piece accompanies our latest update to the Local Government ARPA Investment Tracker, a joint project of Brookings Metro, the National League of Cities (NLC), and the National Association of Counties (NACo). Since 2021, we have monitored how the largest U.S. cities and counties have appropriated, obligated, and spent $65 billion in SLFRF allocations to foster an equitable economic recovery from COVID-19.

This update reflects data from 15,283 projects reported by 336 large local governments (92 cities and 244 counties) to the U.S. Department of the Treasury for program activities conducted through December 31st, 2023. All recipients have until the end of 2024 to obligate their allocated funding and until the end of 2026 to spend it. For more information about how data is collected and analyzed for this project, please visit the dashboard.

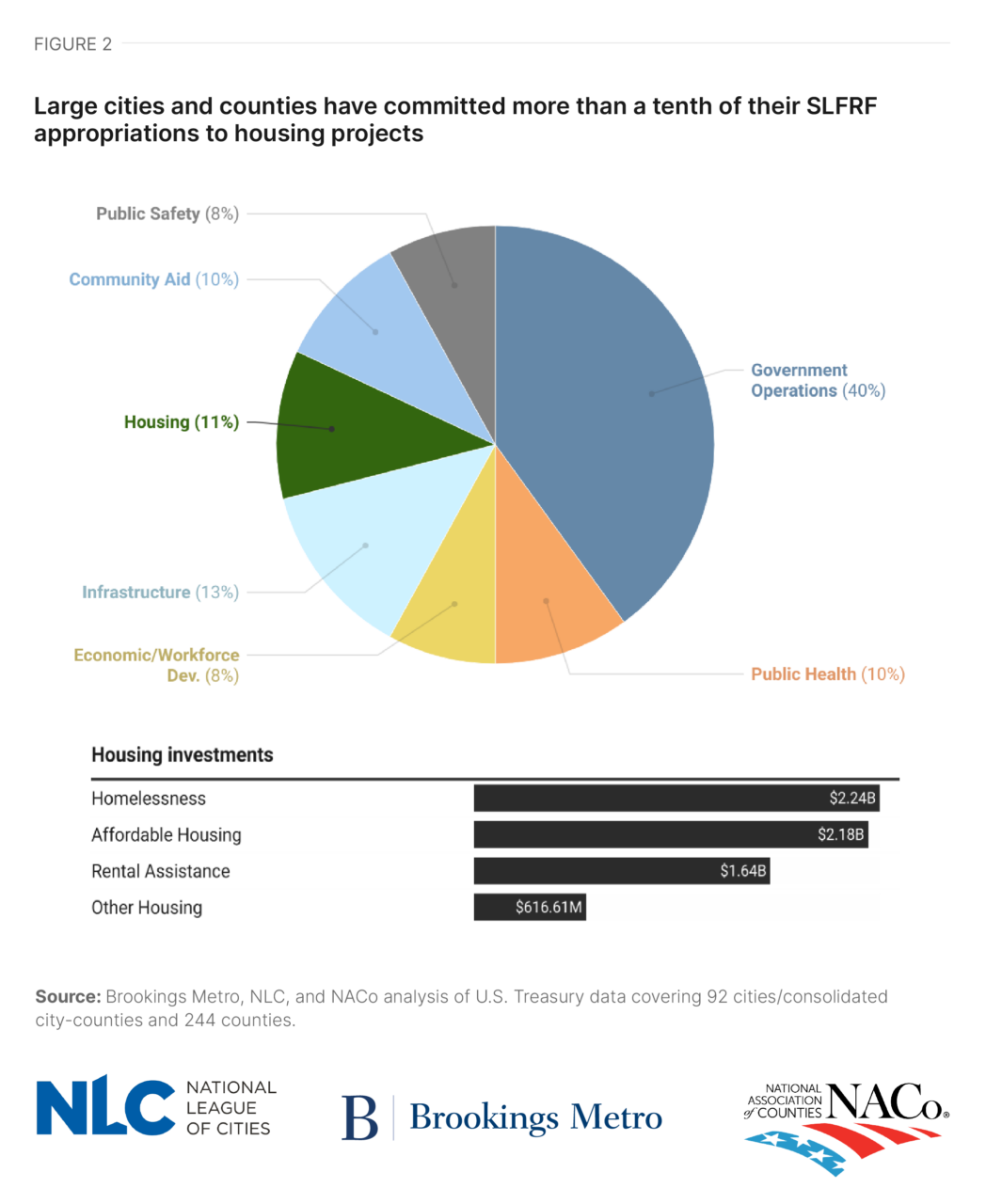

Large cities and counties have committed approximately 10% of total SLFRF funding to housing projects

As of the end of December 2023, large U.S. cities and counties have used the SLFRF program to invest $6.7 billion toward housing projects, accounting for 11% of the $58.8 billion appropriated to date. Roughly two-thirds of these investments have been focused on homelessness services and affordable housing developments. These direct investments in housing have been supplemented by many adjacent programs addressing mental health and substance abuse crises, neighborhood and downtown revitalization initiatives, and other infrastructure projects (such as lead pipe replacements and residential blight remediation). Examples of both direct and supportive investments in housing include:

- Cook County, Illinois’ investment in full-time behavioral health support for residents living in the affordable housing properties managed by the county’s housing authority. Through this behavioral counseling program, the county hopes to promote independent living and full civic participation among individuals with complex behavioral health needs that have negatively affected their ability to maintain stable housing elsewhere.

- Louisville, Kentucky’s downpayment assistance program for households earning less than 80% of the region’s area median income (AMI). Using ARPA funding, the county will provide partially forgivable, interest-free loans to moderate- and low-income residents and households to encourage mixed-use developments that decrease neighborhood income segregation and deconcentrate poverty, and promote homeownership/wealth-building for residents who are not typically able to obtain traditional home loans (such as Section 8 participants).

- Travis County, Texas’ collaboration with local nonprofits on a “supportive housing collaborative” to build new housing units across the county for residents and families currently experiencing homelessness. Beyond building these new units for the county’s unhoused population (which exceeded 6,683 individuals per night in October 2023), this program will also provide mental and physical health, addiction, and restorative justice services to residents to remove barriers that may interfere with their ability to remain stably housed long-term. In a press conference announcing a $35 million contract with a local nonprofit to carry out part of this initiative, Travis County Judge Andy Brown summarized this whole-of-person approach to the housing crisis as an acknowledgment that “Austin has an affordability crisis, but it doesn’t have to have a moral one too.”

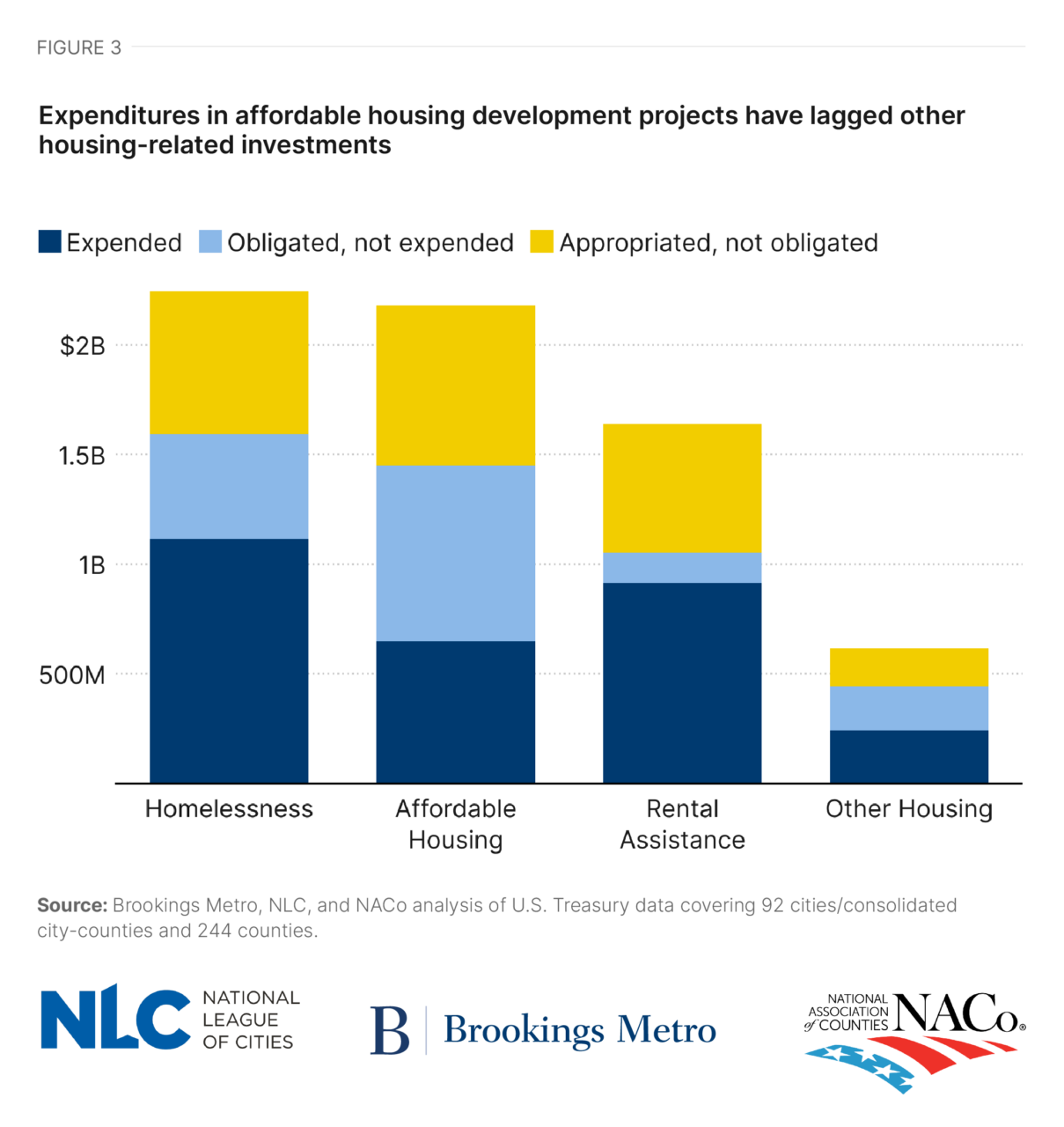

Affordable housing obligations are on par with other SLFRF investments, but expenditures have lagged

These appropriations represent a significant local commitment to addressing housing-related distress. However, funding committed for affordable housing development has been comparatively slow to reach the communities such projects are designed to help. Though obligations for affordable housing projects have largely kept pace with appropriations—meaning local governments have been making headway in selecting contractors and service providers to deploy these committed funds—expenditures have lagged. As of the end of 2023, affordable housing accounted for one-third of all dollars committed to housing projects but just over a fifth of expenditures made toward these projects.

In some instances, these delays are occurring where commitments to affordable housing development have been strongest. For example, in Madison, WI – where home values grew 14% between 2022 and 2023 – city officials have committed 66% of their SLFRF investments to date toward affordable housing, financial recognition of what Dane County mayors have called “the defining problem of the region.” Yet, as of December 2023, the city has yet to expend any of the dollars they appropriated to these projects. A similar situation prevails in Cumberland County, NC, which has experienced a surge in homelessness caused by evictions in and around the City of Fayetteville. Despite affordable housing accounting for one-fifth of the county’s SLFRF appropriations, none of this funding has been spent.

Importantly, these delays are not necessarily a reflection of public sector commitment or capacity. Capital-intensive investments in new housing have much longer time horizons than other housing-related projects, such as those that invest in services for unhoused populations. It is also worth noting that obligations for housing projects, including affordable housing, have mostly kept pace with other SLFRF investment priorities—as of December 2023, 68% of funding for housing projects had been obligated, compared to 70% for all SLFRF projects. These projects are at no greater risk of falling short of Treasury’s December 2024 deadline than other types of SLFRF investments.

Local governments have many tools to enhance housing affordability

The federal government has limited direct authority over housing production, which is why the SLFRF program’s influx of federal funding to local governments is such a notable development. Indeed, this investment is comparable in size to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s HOME Investment Partnerships program, one of the federal government’s largest flagship housing grants. However, as this analysis shows, affordable housing takes time to plan, design, and construct, making it a particularly important area of focus for local governments as they approach the SLFRF obligation deadline at the end of 2024. While ARPA alone will certainly not fix the U.S. housing market, the timely and equitable deployment of funding already committed to resolving these issues can provide critical relief to renters and homeowners alike.

Notwithstanding the importance of delivering on SLFRF, local governments control many levers that influence housing affordability, even in the absence of additional federal funding. Local governments – and their states – are responsible for zoning, building codes, and other policies that greatly impact housing development and maintenance. As our Brookings Metro colleague Jenny Schuetz has written, local governments can enhance affordability by relaxing restrictions on market-rate housing development and launching new experiments to increase the supply of housing accessible to low-income renters. If localities are unwilling to do so, state governments can step in with their own reforms.

The bottom line is that by making the most of federal funds and local policy reforms, governments at all levels can work together to address the complex challenge of housing affordability and ensure that all residents have access to safe and affordable housing options.

The authors thank Alan Berube, Teryn Zmuda, Christine Baker-Smith, and Ricardo Aguilar for their research advice and support.

Glossary Of Terms

- Allocations are the total funds distributed to state and local governments through the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program.

- American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) is the $1.9 trillion economic stimulus and pandemic recovery legislation signed into law by President Joe Biden on March 11, 2021. This legislation is also referred to as the “American Rescue Plan” or “ARPA.” This brief focuses solely on the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) program, and thus, “ARPA” and “SLFRF” are used interchangeably.

- Appropriations are dollars distributed to state and local governments through the SLFRF program that has been budgeted or committed to specific initiatives or programs. In this brief, “appropriations,” “investments,” and “commitments” are used interchangeably.

- Coronavirus State And Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) is the $350 billion program authorized by the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) that provides economic stimulus and pandemic recovery funding to U.S. states, territories, cities, counties, and tribal governments. This brief focuses solely on the SLFRF program, and thus, “ARPA” and “SLFRF” are used interchangeably.

- Obligations are dollars distributed to state and local governments through the SLFRF program that have been legally dedicated to specific uses, frequently (but not exclusively) through contractual agreements. The Treasury Department’s newest guidance defines obligations as “orders placed for property and services and entry into contracts, sub-awards, and similar transactions that require payment.” The Final Rule requires recipient cities and counties to obligate 100% of their SLFRF allocations by December 2024.

- Revenue Loss is a provision of the SLFRF Final Rule that allows local governments to classify some or all of their allocations as “revenue replacement.” Local governments may claim up to $10 million as “revenue replacement” as a standard allowance without any requirement to demonstrate a loss of revenue or more if they are able to demonstrate a loss of revenue attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Revenue Replacement is an eligible use classification established in the SLFRF Final Rule. Funds classified as “revenue replacement” through the SLFRF program’s revenue loss provision can be used for any government service permissible under state law and are not subject to many SLFRF programmatic reporting requirements.

- Tier 1 Local Governments are metropolitan cities and counties with populations greater than 250,000. These jurisdictions are also referred to as “large local governments” or “large cities and counties.”