Authored by by Juliet L. King PhD, ATR-BC, LPC, LMHC

Public-facing figures are taxed by balancing personal privacy with their public roles. The stress of maintaining a public image, coupled with criticism, can lead to significant emotional strain. In 2021, “8 in 10 surveyed local elected officials reported experiencing harassment, threats, and violence.” As local officials tasked with making critical decisions for your communities, ensuring your own well-being is essential. Engaging in creative activities offers a valuable outlet for local municipal officials to manage these pressures, providing a way to explore and express emotions, build resilience and maintain mental well-being amidst the demands of public life.

Art-making (visual art, movement, music, etc.) allows individuals to externalize and concretize thoughts, memories, and feelings, which can offer a sense of objectivity and distance. Expressing yourself creatively engages key brain networks that can boost emotional well-being and promote the integration of thoughts and feelings. This helps us to see our experiences from a new perspective and encourages new ways to navigate challenges.

On the surface, it seems simple: creative expression makes us feel good. What’s happening in our brains, however, is incredibly complex. When we engage with art — whether that’s creating it ourselves or experiencing art created by others — our brains use fewer cognitive resources, allowing us to express ourselves more freely and creatively. Engaging with art can lead to reduced anxiety, improved mood and enhanced cognitive function. Studies have shown that creative expression activates the brain’s reward system, releasing feel-good chemicals like dopamine. This isn’t just about feeling good; it also reinforces positive behavior, encourages motivation and helps us cope with uncertainty.

In short, creativity is a natural state of being, one that our brains are wired to seek out and enjoy.

You can experience the mental health benefits of creativity by working with a credentialed art therapist. Creative arts therapists also work through drama, dance, music, film or visual art. However, one does not need to work with a therapist to experience the benefits of the arts.

A Simple Exercise for Stress Relief

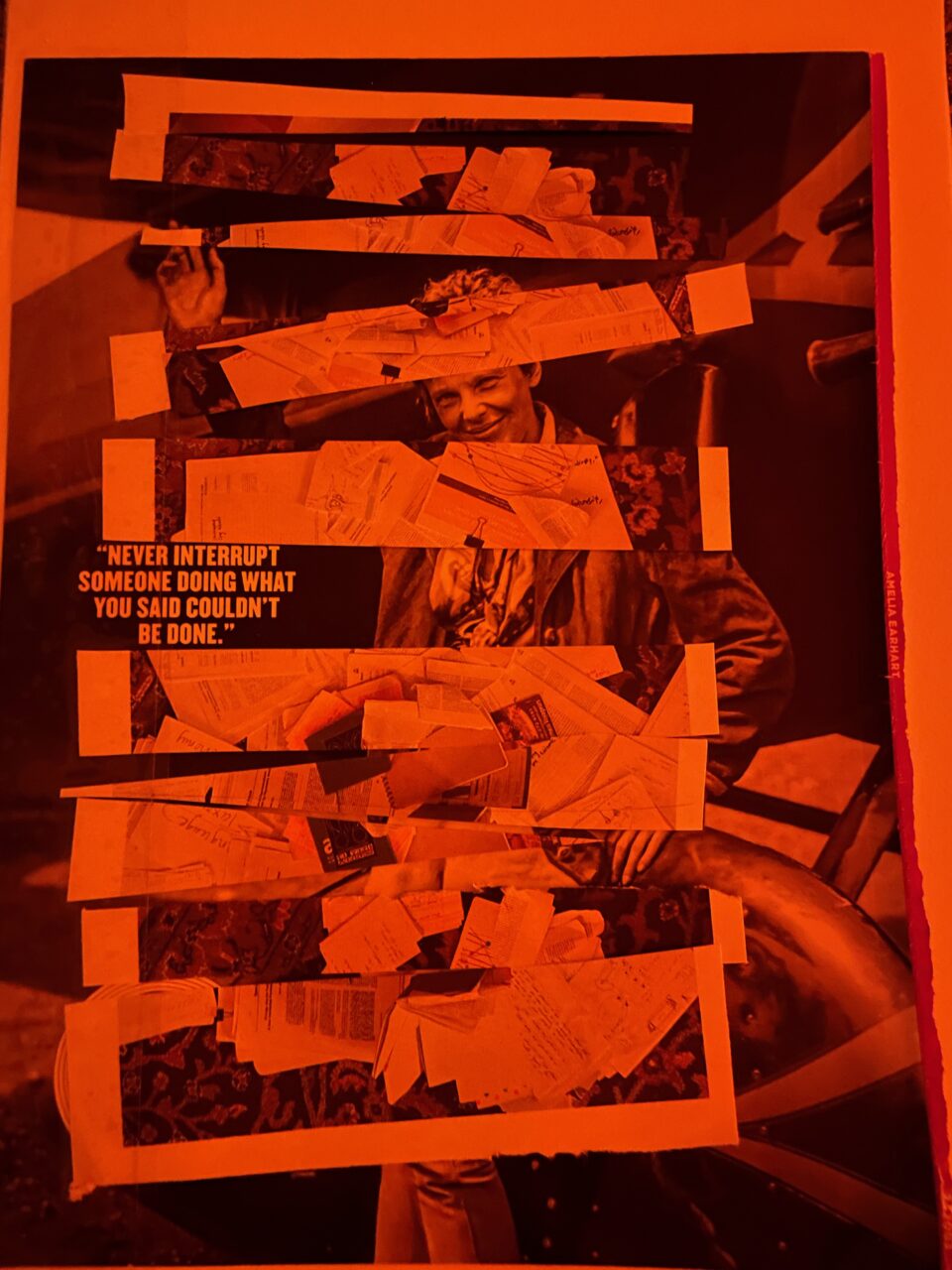

To help you experience the benefits of art firsthand, here’s a simple self-directed exercise designed to alleviate stress and promote relaxation. This exercise is modified from an art therapy intervention (Tripp, Potash, & Brancheau, 2019) called the Safe Place Collage.

Note from the artist: “For me, creating the image was both enjoyable and difficult. I paid attention to how much I avoided looking at disturbing images. In doing so I realized that I preferred to indulge in my imagination. Overall, the process gave me confidence which inspired hope and what I made makes me happy.“

Materials Needed:

These are general suggestions — you are encouraged to pull from what you have and what makes sense to you at the time.

- Collage items (images from magazines, newspapers, or printed from online sources — consider also stickers, old greeting cards, etc.)

- Paper (9×12 is ample)

- Glue stick, mod podge, rubber cement, packing tape, etc.

- Scissors, X-Acto knife

- Markers (a set of 12 with both thick and thin tips) or other drawing materials you have

Instructions:

- Select Your Images: Begin by selecting one image that represents a positive resource of safety or comfort for you. This could be a serene landscape, a symbol of protection or anything that evokes a sense of calm. Next, choose another image that represents something mildly disturbing or uncomfortable — something that might be causing you stress or unease.

- Create Your Collage: On the paper, start by gluing the comforting image in a central or prominent position. Then, integrate the disturbing image into the collage. The goal is to create a piece of artwork that harmonizes these contrasting elements, helping you to process and manage the stressor within a context of safety.

- Add Personal Touches: Use the markers to add details, words or other artistic elements that help you express your emotions. You can use thick lines to emphasize strength and stability, or thin lines to depict delicate, calming details. Get creative with stickers and other things laying around!

- Reflect: Once your collage is complete, take a moment to reflect on the process. Consider how integrating these images made you feel. Did the act of creating help you gain new insights or alleviate stress? How can this exercise inform your approach to managing future stressors?

By taking a few moments to engage in this creative exercise, you can tap into the therapeutic power of the arts to enhance your mental well-being. Reflecting on what you create, and the process of its creation, fosters insight, self-awareness, objectivity and clarity. This safe, non-threatening way of paying attention to yourself helps connect action with perception and behavior. The beauty of artistic expression lies in its ability to help us process complex emotions and find balance, even amid challenges. Incorporating simple, self-directed art activities into your routine can be a powerful way to support your mental health and maintain resilience in your important work.

Can A Board Game Make You A Better City Leader?

Are you tired of your council meetings or retreats feeling dry and procedural? Do you wish you could inspire more cohesion and agreement at public town hall meetings? Try playing a board game. Learn how a simple board game inspired more cohesion and agreement at public town hall meetings in Parker, CO.

Juliet L. King, PhD, ATR-BC, LPC, LMHC, is an Associate Professor of Art Therapy at The George Washington University and an Adjunct Associate Professor of Neurology at Indiana University School of Medicine. Dr. King’s research focuses on the integration of art therapy and cognitive neuroscience with a specialization in psychological trauma.

References

- Bone, J.K., & Fancourt, D. (2022). “The mental and physical health benefits of the arts: A review of the evidence.” Journal of Health Psychology, 27(3), 375-389. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10154961/

- Davies, C., & Clift, S. (2022). “Arts and health: A review of the evidence base for its impact on health and well-being.” Public Health, 202, 100-110. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.949685

- De Witte, M., Orkibi, H., Zarate, R., Karkou, V., Sajnani, N., Malhotra, B., & Koch, S. C. (2021). From therapeutic factors to mechanisms of change in the creative arts therapies: A scoping review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 678397. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678397/full

- Fancourt, D., & Finn, S. (2019). “What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review.” World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553773/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK553773.pdf https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2535-7913-2020-01-08

- King, J. L., & Parada, F. J. (2021). Using mobile brain/body imaging to advance research in arts, health, and related therapeutics. European Journal of Neuroscience, 54(12), 8364-8380.

- Shafir, T., Orkibi, H., Baker, F. A., Gussak, D., & Kaimal, G. (2020). Editorial: The State of the Art in Creative Arts Therapies. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00068

- The Aspen Institute. (2021). NeuroArts Blueprint. Advancing the Science of Arts, Health, and Wellbeing. The Aspen Institute. https://neuroartsblueprint.org/wpcontent/uploads/2021/11/NeuroArtsBlue_ExSumReport_FinalOnline_spreads_v32.pdf

- Tripp, T., Potash, J. S., & Brancheau, D. (2019). Safe Place collage protocol: Art making for managing traumatic stress. Journal of trauma & dissociation, 20(5), 511-525. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2019.1597813